Ilan Manor, uscpublicdiplomacy.org

uncaptioned image from article

When foreign ministries first migrated online, they viewed social media platforms as mass media channels. Much like radio and television, Twitter and Facebook could be used to disseminate messages among millions of users. Subsequently, the focus of online activity was mass information dissemination, while the parameter for success was audience reach. MFAs relied mostly on general engagement parameters such as the number of followers they attracted on social media, the number of retweets their messages garnered and their overall reach online.

However, foreign ministries soon learned that social media was quite different from other mass mediums (e.g., radio, television). This was because users could react to diplomats’ content and even hijack that content for their own purposes. One notable example was Sweden’s launch of a virtual embassy on Second Life. Sweden’s goal was to open a global embassy that could showcase Swedish art and culture. However, some Second Life users saw the embassy as a state-sponsored invasion of virtual space and protested the embassy’s presence.

What followed was the realization that social media was a two-way medium with interaction between messenger and recipient. While some diplomats feared the power of online masses, others saw an opportunity to better craft diplomatic messages. By using the feedback of social media users, diplomats could identify which elements of their foreign policy were contested or negatively viewed. Moreover, diplomats could use online comments to better understand how their nation was viewed in various parts of the world.

Thus began the age of digital diplomacy 2.0.

What characterized digital diplomacy 2.0—which began circa 2014—was the transition from targeted to tailored communication. Foreign ministries were no longer occupied with reaching masses of audiences but with reaching specific audiences. Moreover, foreign ministries aimed to tailor their messages to the interests and beliefs of these specific audiences. For instance, foreign ministries sought to interact with opinion makers such as journalists, bloggers and other diplomatic institutions. Thus, they were no longer occupied with how many followers they attracted online but with how many diplomats and journalists they attracted. By 2016, foreign ministries and embassies were using network analysis to identify and interact with specific audiences while adjusting their evaluation parameters.

Yet it was 2017 that has seen the slow emergence of the next stage of digital diplomacy: personalized diplomacy.

Digital Diplomacy 3.0: Personalized Diplomacy

The third and current stage of digital diplomacy is that of personalized diplomacy. It is during this stage that foreign ministries and diplomats will attempt to create a diplomatic experience that is tailored to the individual. Such tailoring may center on the user’s interests, needs or patterns of technology use.

By offering users a personalized experience, the MEA increases the likelihood of users returning to the application, engaging with MEA content and sharing what they have learned with online contacts.

One interesting example is a smartphone application developed by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). The MEA is not the first foreign ministry to launch its own application; both the Polish and the Canadian ministries have launched apps. However, while the Canadian application focuses on consular aid, the MEA’s application focuses on supplying digital services and information to users. Moreover, unlike the Canadian application which is relevant only to Canadian citizens, the MEA application seems to target both domestic and foreign populations.

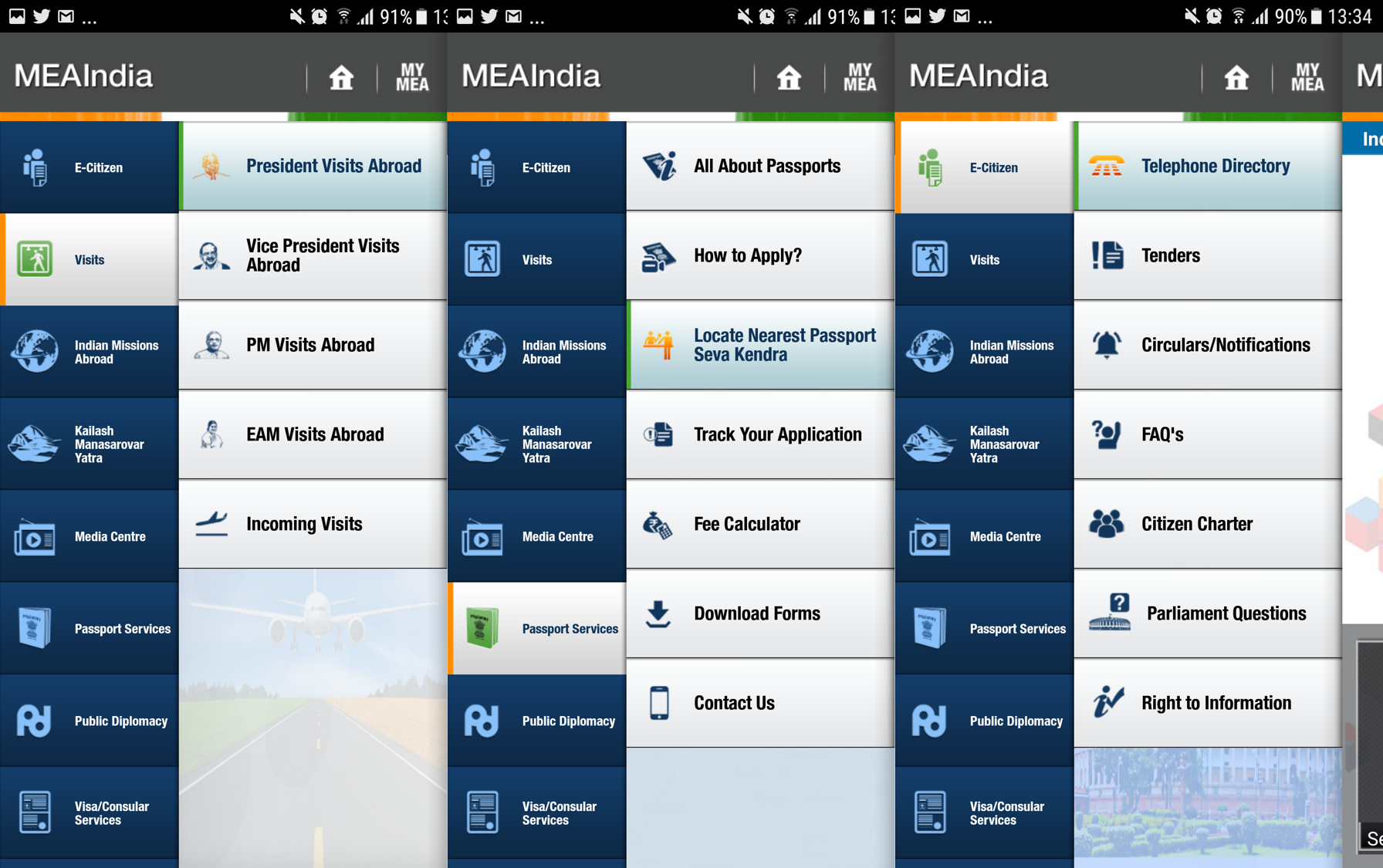

The application has seven features. The first is the e-Citizen feature that offers e-services to Indian citizens ranging from telephone directories to employment opportunities at the MEA.

The second feature enables users to track state visits by Indian officials abroad as well as state visits by foreign dignitaries to India. The scope of available information is substantive, ranging from images to bilateral and multilateral documents signed during state visits as well as public statements made by world leaders. The third feature enables users to locate the nearest embassy to them, to read updates from embassies and even to hear podcasts by Indian ambassadors. The fifth feature is the media center which consists of a wide array of documents, press releases, speeches, statements and transcripts of media briefings.

The sixth feature is a consular one. It is in this feature that a user can apply for visas, track his or her application, download forms and even communicate with the MEA. The seventh and final feature focuses on public diplomacy. It is under this feature that a user can hear lectures on Indian diplomacy from former ambassadors, watch documentaries on India or read issues of the MEA’s magazine, India Perspectives.

The review of the MEA’s application thus far suggests that it offers a breadth of information. However, the most interesting feature of the application is its personalization mechanism. Each user can create his or her own MEA application by selecting the specific issues he or she wishes to follow more closely. Users even have a notepad where they can write comments on the information they have reviewed.

This form of digital diplomacy offers users a personalized digital experience that is tailored to their interests and needs. Journalists can follow press briefings and state visits while prospective tourists can follow embassy updates and track their visa application. Users can even interact with the MEA through the various modules. By offering users a personalized experience, the MEA increases the likelihood of users returning to the application, engaging with MEA content and sharing what they have learned with online contacts.

Where to Next?

The practice of digital diplomacy 3.0 will likely continue to take shape in coming years. This process may be facilitated by a host of new technologies. Virtual and augmented reality may soon enable users to virtually travel to other countries and experience their culture and history. Such trips will be personalized and will offer each user an experience that matches his or her specific interests. Artificial intelligence will be employed to communicate with online users and best meet their consular needs while smartphone applications will send users notifications tailored to their occupational needs.

Importantly, foreign ministries should invest in developing personalized forms of digital diplomacy, given that online users are already accustomed to personalized online experiences when logging onto Netflix, Amazon or Pizza Hut.

No comments:

Post a Comment