Katarzyna Rybka-Iwanska, uscpublicdiplomacy.org

In November, the CPD Blog published Knowledge Diplomacy Part I: The Game Over Talents Goes Global, which addressed the global character of competition over the world’s brightest minds.

Part II will focus on developing countries. Soon, they may transition from competition newcomers to game changers. Here are several micro-trends explaining why we should think so:

Africa

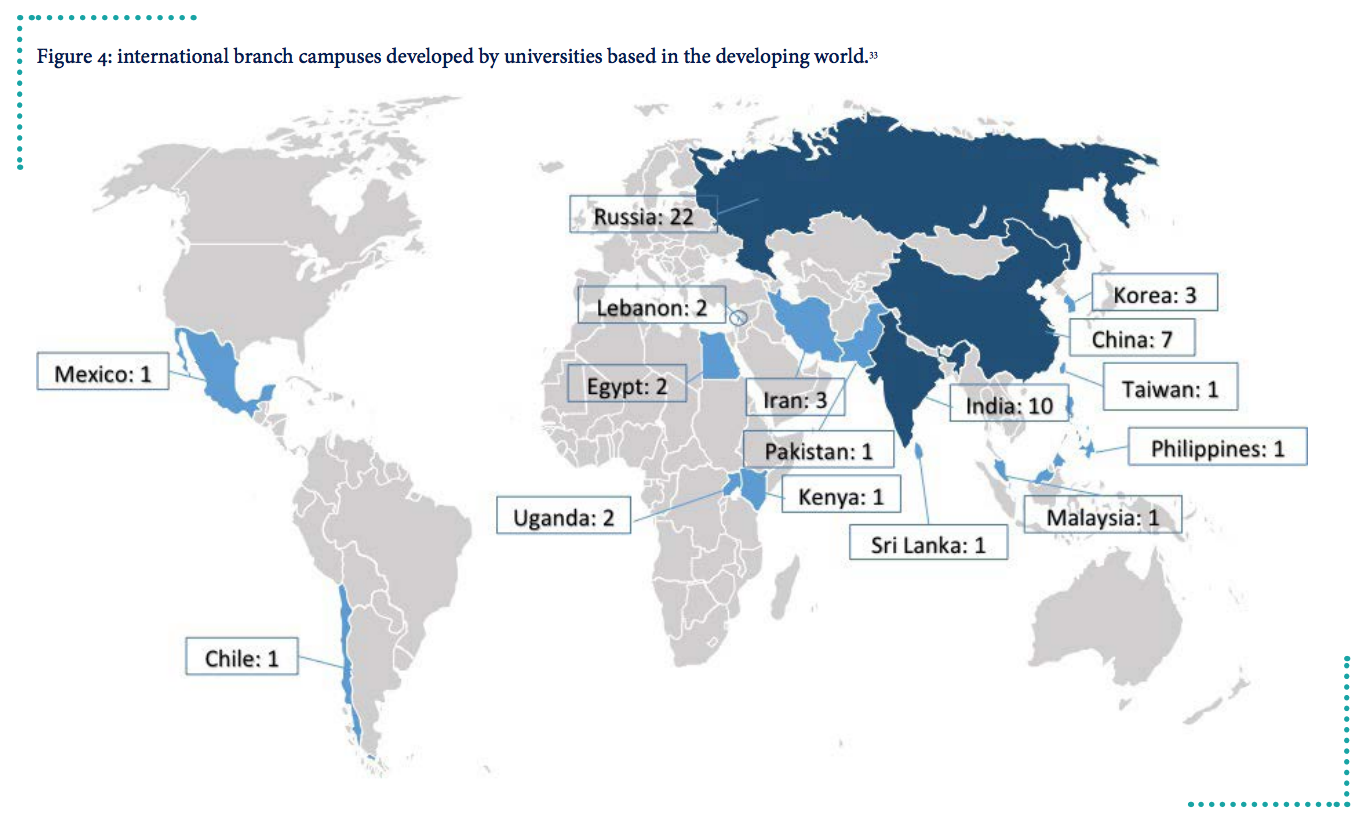

As mentioned in Part I, the University of Oxford recently published the study, International Trends in Higher Education 2016-2017, focused primarily on “the growing confidence of leading universities in developing countries to build an international profile.” It refers to case studies of Russian universities opening branch campuses in former Soviet states, Xiamen University opening a branch in Malaysia, Peking HSBC Business School starting to operate near Oxford in the UK, and Mumbai University searching for a branch location in the U.S. (image below on page 12).

The study also shows China’s large education and training investments in Africa. Following Xi Jinping’s appeal to focus more on soft power that echoed globally in 2014, China has funded tens of thousands of scholarships for African students and some 200 visiting placements for African scholars, as well as thousands of training opportunities in Chinese organizations and companies. There are also 46 Confucius Institutes operating in 30 African countries.

The African market of higher education and training keeps expanding. The study highlights the Nigerian example: “In Nigeria in 2015, the number of applicants for university places was twice as large as the number of available seats; partly as a result, the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent […] between 2005 and 2015. This trend is set to continue, making Nigeria the fastest-growing source of mobile students: tertiary enrolment among Nigerians is projected to double from 2.3 million students in 2013 to 4.8 million in 2024.”

Asia

Educational capacity in developing countries is constantly growing, and as the report states, it can meet demands in the 2020s in Asia and Latin America. This has significant implications for Western educational institutions, in part because a trend among students from developing countries to enroll in universities closer to home is visible. Ghana is already a second destination for Nigerian students. Moreover, according to the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI) 2015-2016, Indian and South Korean students more and more often choose China over the U.S., partly due to the U.S.’s strict visa regulations when post-diploma employment is concerned.

Even though a broader Asia is traditionally regarded as an exporter of talents, an interesting trend has started to emerge.

According to the GTCI 2015-2016, “talent who have left their country of origin are returning home to Asia, bringing with them valuable global experience, knowledge, skills, expertise and networks. … [T]he axiom today is to ‘look West for world-class education and look East for a global career,’” which is a result of mediocre economic trends in the West and opposite ones in Asia.

Especially in many developing countries, cities are often more pragmatic and agile than national governments.

The biggest Asian player, China, tries to implement policies that will bring the brightest Chinese minds back to the country and promises the abovementioned global career in Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou. However, the state’s policies do not seem to succeed rapidly: the GTCI 2015-2016 notes, “85% of Chinese people who earned their science or engineering doctorates in the United States in 2006 were still there in 2011.”

China intends to change its business culture and corporate practices which will eventually help bring talents back home.

The ASEAN region also serves as an interesting example. Even though it is overwhelmed by Singapore’s massive investments in attracting talent, some countries find their own way into the field. Malaysia, for example, has systematically advanced (the GTCI reports Malaysia in 35th place for 2014, and 28th place for 2017). More and more skilled employees from Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines settle in Malaysia due to opportunities stemming from industrialization and urbanization (not yet from a long-term vision and public policies, though, as Malaysia performs badly in terms of tolerance for minorities and immigrants).

Cities

The role of cities cannot be overestimated in the 21st century, when non-state actors increase their role in international relations. Especially in many developing countries, cities are often more pragmatic and agile than national governments. That is why, for instance, São Paulo conducts unique diplomatic relations with more than 100 countries who often post more diplomats there than in Brasilia.

Beyond global cities that attract talents, “digital nomads” are able to work from anywhere in the world, do not feel obliged to pick metropolises for their place of stay—they will go wherever costs of life are cheaper, weather and climate conditions are good, and their children (if they have them) have access to good education, of course.

Santiago de Chile, another interesting example from South America, tries to build on that. Following certain public policies, Santiago de Chile has been called “Chilecon Valley,” particularly due to improving business environment and good living conditions, including for ex-pats. It is estimated that there are investors from 79 countries operating there today. Chilecon Valley does not place an emphasis on pulling international students, though, and focuses instead on technological bright minds that are already in the labor market.

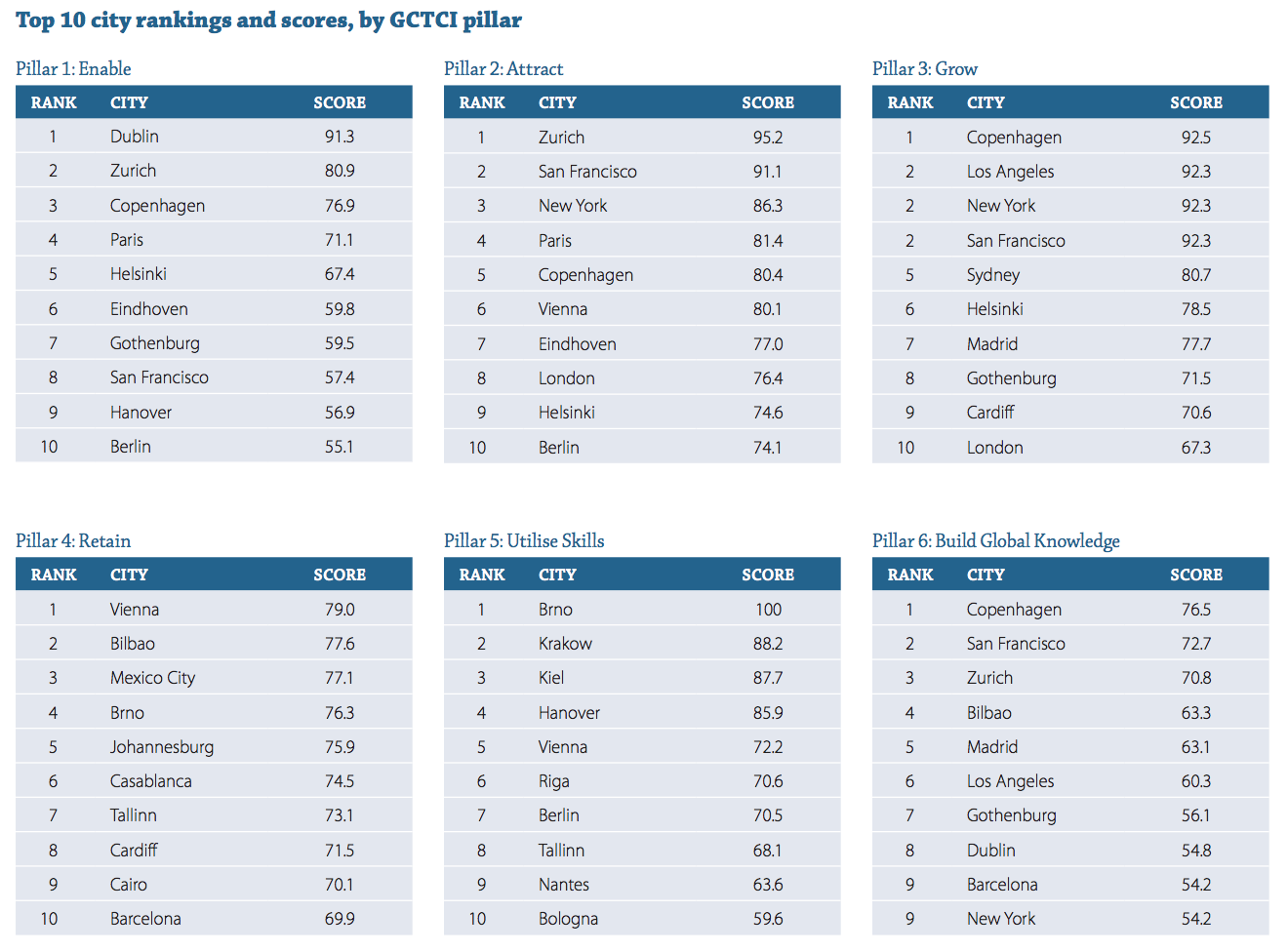

As for international rankings, the Global City Talent Competitiveness Index 2017 acknowledges cities like Copenhagen, Zurich or San Francisco that are located in highly developed countries.

However, some stakeholders representing developing nations perform well. For instance, in the “Retain” pillar (below, or GCTCI Index page 108), Mexico City is 3rd, Johannesburg is 5th, Casablanca is 6th and Cairo is 9th.

Where the R&D performance of cities is concerned, the Global Power City Index 2017 remains dominated by the “usual suspects,” but cities like Beijing, Moscow, Istanbul and Bangkok have already made it to the top 30.

The global picture is changing in the direction of more diversity and more individually tailored solutions.

It is said that in the future, employment will go where the talent is. This type of mobility will be temporary-oriented, meaning that jobs will be based on particular projects conducted by contemporary nomads rather than through long-term engagements.

This trend, including its consequences for states, cities and their public diplomacies, will be examined more broadly in the third installment of this series for the CPD Blog.

Photos (from top to bottom): Photo by Alexas_Photos I CC0; Image on page 12 of the International Trends in Higher Education 2016-2017 study; Image on page 108 of The Global Talent Competitiveness Index 2017

Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This article is Part II of a three-part series on knowledge diplomacy as a significant soft power tool, with a focus on major trends defining international relations in the field of talent and knowledge. Read Part I.

No comments:

Post a Comment