Cold War Museum; via TL (many thanks!)

In 1951, the Voice of America (VOA), which was at that time located primarily in New York but managed from Washington by the State Department, was under heavily criticism, particularly from Republicans in the U.S. Congress, for failing to counter Soviet propaganda. There was a spirited debate as to whether VOA should continue to offer primarily non-political programs about America, or whether it should join recently established Radio Free Europe with more hard-hitting American opinions about communism, the Soviet Union, and communist China.

In 1951, the Voice of America (VOA), which was at that time located primarily in New York but managed from Washington by the State Department, was under heavily criticism, particularly from Republicans in the U.S. Congress, for failing to counter Soviet propaganda. There was a spirited debate as to whether VOA should continue to offer primarily non-political programs about America, or whether it should join recently established Radio Free Europe with more hard-hitting American opinions about communism, the Soviet Union, and communist China.With President Truman, a Democrat in the White House in 1951, Democrats tended to be more supportive of VOA and Republicans tended to to more critical, but the bipartisan consensus in Congress was that the management of the Voice of America needed reforms and that VOA programming must become more relevant to the people living without freedom behind the iron and bamboo curtains.

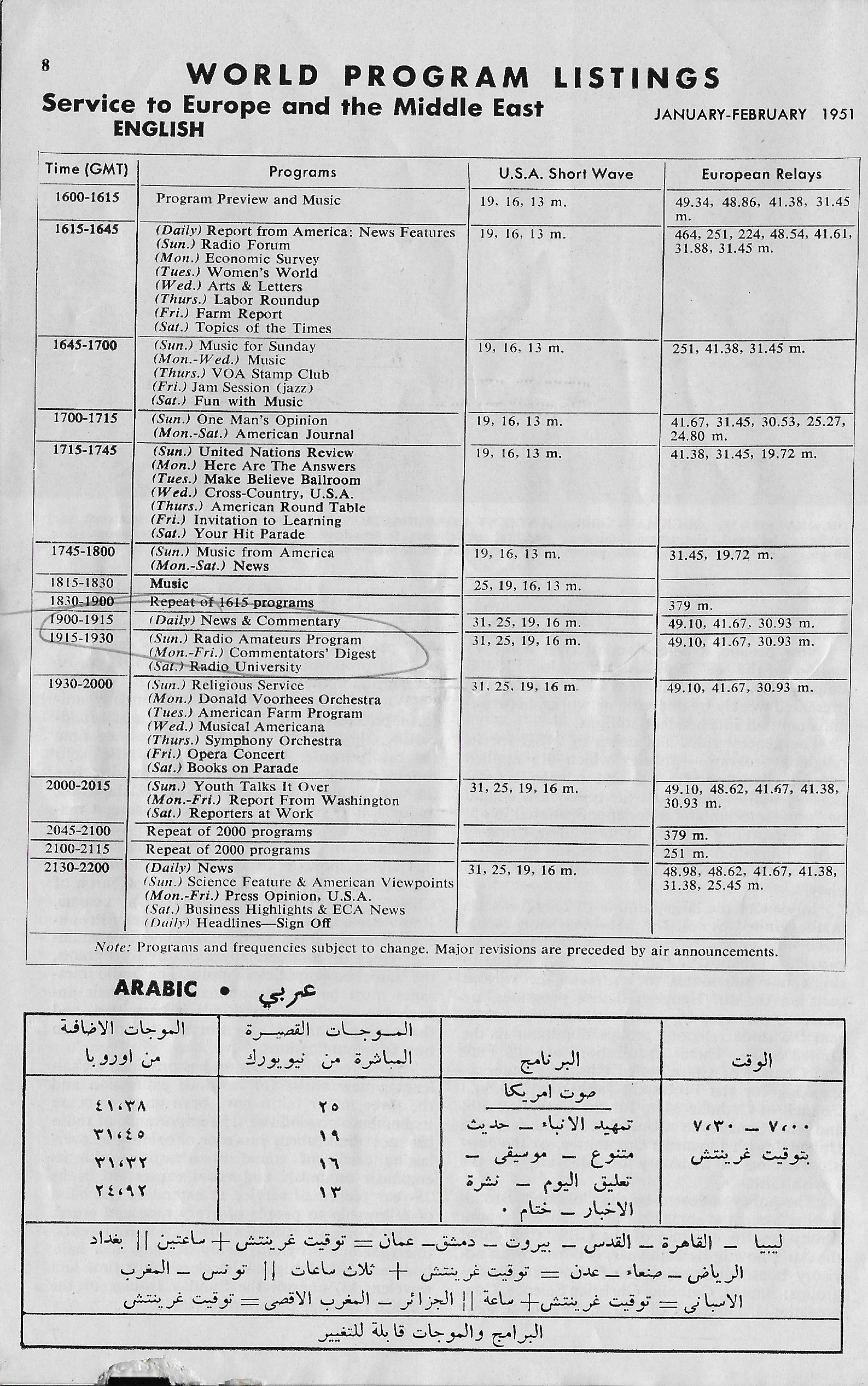

By 1951, VOA was already moving in the direction of more political reporting and commentary about the threat of Soviet and Chinese communism, but such content, with a few minor exceptions, was not yet reflected in the Voice of America January-February 1951 Program Schedules brochure which included feature articles about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

VOA is “as hard-hitting as a creampuff,” one U.S. lawmaker observed on the House floor in July 1951 during a debate of the State Department’s budget for overseas radio broadcasting.[1] He accused VOA officials in the State Department of vastly overstating VOA’s impact by presenting “grandiose figures on the size of the audience that supposedly is listening to the Voice around the world.”[2]

Two of the seven feature articles in the January-February 1951 VOA brochure were about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, most likely because Washington’s Birthday, called Presidents’ Day since 1971, is celebrated in the United States on the third Monday in February. Abraham Lincoln’s birthday is also in February.

Judging from the debates in the U.S. Congress in 1951, most lawmakers and other critics did not specifically object to features about American democracy in VOA programs, but they did not want them to be the exclusive content of U.S. taxpayer-funded broadcasts for overseas audiences. Their concern that the Voice of America was ineffective in countering Soviet propaganda was shared by many prominent Americans. Former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane, who became a champion of creating Radio Free Europe and also advocated personnel and programming reforms at VOA, observed already in 1948:

AMB. ARTHUR BLISS LANE: As for radio broadcasts beamed to Poland as the “Voice of America,” my opinion of their value differed radically from that of the authors of the program in the Department of State. …I felt that the Department’s policy to tell the people in Eastern Europe what a wonderful democratic life we in the United States enjoy showed its complete lack of appreciation of their psychology. And, especially in Poland, which had suffered through six years of Nazi domination, it was indeed tactless, to say the least, to remind the Poles that we had democracy, which they also might again be enjoying, had we not acquiesced in their being sold down the river at Teheran and Yalta.[3]

Ambassador Lane wrote that he did not object to U.S. sponsored radio broadcasting to reach the countries behind the iron curtain if appropriate material is used which will bring hope instead of intensifying despair. “But the wisdom of statesmanship, not that of salesmanship, is a requisite,” he observed.[4] His advice is just as relevant now as it was in the late 1940s.

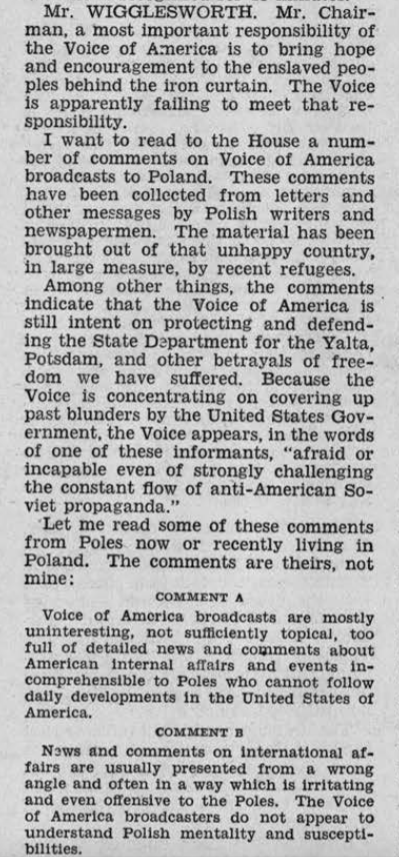

During debates in Congress in 1951 on the budget for VOA and State Department’s public diplomacy programs, a longtime critic of the Voice of America, Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-MA) disclosed that listeners to VOA broadcasts in Poland described them as “uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing,” the same kind of criticism as that voiced by Ambassador Lane.

During debates in Congress in 1951 on the budget for VOA and State Department’s public diplomacy programs, a longtime critic of the Voice of America, Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-MA) disclosed that listeners to VOA broadcasts in Poland described them as “uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing,” the same kind of criticism as that voiced by Ambassador Lane.Mr. WIGGLESWORTH. Mr. Chairman, a most important responsibility of the Voice of America is to bring hope and encouragement to the enslaved peoples behind the iron curtain. The Voice is apparently failing to meet that responsibility. I want to read to the House a number of comments on Voice of America broadcasts to Poland. These comments have been collected from letters and other messages by Polish writers and newspapermen.

The material has been brought out of that unhappy country, in large measure, by recent refugees. Among other things, the comments indicate that the Voice of America is still intent on protecting and defending the State Department for the Yalta, Potsdam, and other betrayals of freedom we have suffered. Because the Voice is concentrating on covering up past blunders by the United States Government, the Voice appears, in the words of one of these informants, “afraid or incapable even of strongly challenging the constant flow of anti-American Soviet propaganda.” Let me read some of these comments from Poles now or recently living in Poland. The comments are theirs, not mine:

COMMENT A

Voice of America broadcasts are mostly uninteresting, not sufficiently topical, too full of detailed news and comments about American internal affairs and events incomprehensible to Poles who cannot follow daily developments in the United States of America.[5]

“They give the impression that they are prepared and spoken by clerks who do their job perfunctorily without any intelligent understanding of the human element or of Polish susceptibilities,” Wigglesworth read from letters received from VOA listeners in Poland.[6]

Congressman Wigglesworth was a Harvard-educated lawyer who served as captain in Europe during World War I, worked in Europe after the war, and after his longtime service in the U.S. House of Representatives was U.S. Ambassador to Canada at the end of his public career.

Another lawmaker, Congressman John V. Beamer (R-IN), disclosed results of a survey obtained by the U.S. Embassy in Havana which showed VOA with near zero audience in pre-Castro Cuba. Congressman Beamer said on the House floor on July 24, 1951:

CONGRESSMAN JOHN V. BEAMER: The Voice of America is not reaching the the people of the world. The United States is falling down on psychological weapons, which should be one of our mainstays. I repeat, most Members of this House agree on the urgent need for a hard-hitting Voice that will bring the story of freedom and democracy to the other peoples of the world. Day by day, the evidence is mounting that the Voice of America, as now managed and operated, is about as hard-hitting as a creampuff. Improvements certainly are necessary.[7]

Congressmen Wigglesworth’s and Beamer’s criticism of VOA was partially disputed by Polish-American members of Congress, Alfred D. Sieminski (D-NJ) and Clement J. Zablocki (D-WI). They both said they were interviewed by VOA and concluded that VOA programs were effective.

VOA officials had discovered that interviewing members of Congress tended to blunt their criticism.

“Of course, we know that they cannot reach all of the world with the appropriations we are giving them, but they are doing a very good job with the amount of money they have,” Congressman Zablocki said in response to critical comments about VOA by Congressman Beamer.[8]

But not everyone was persuaded by PR efforts of State Department and VOA personnel. Another Polish-American member of Congress, Thaddeus M. Machrowicz, a Democrat from Michigan, joined Republicans in criticizing VOA broadcasts despite being interviewed earlier by VOA.

It should be noted that the term “propaganda,” as used then by Congressman Machrowicz and other members of Congress, did not have the same negative connotations in 1951 that it has now.

CONGRESSMAN THADDEUS M. MACHROWICZ: I have made an attempt to learn more of the workings of that organization and have even participated in several broadcasts to Poland and its people.

I have come to the conclusion that the people at the head of this service have not fully understood their mission. That mission, in my opinion, is not necessarily to convince those victims of Soviet aggression what a wonderful country and system we have in the United States. That is not what they are waiting to hear. What they want to know and what they have been waiting for in vain, is to learn from us what hope there is for them for eventual liberation from the shackles of tyranny and oppression. It is of little comfort to them to learn of the fine conditions existing here in the United States, as long as they have a feeling that there is no possibility that their own plight will be improved.[9]

Congressman Machrowicz, most Republicans and almost all Democrats in the U.S. Congress in 1951 did not want to abolish the Voice of America but were demanding better performance and effectiveness, better management, and more accountability.

CONGRESSMAN THADDEUS M. MACHROWICZ: I cannot, however, agree with the logic of the gentleman from Ohio [Mr. BROWN], who proposes to do with this bill what he and his party have succeeded doing last week to the Defense Production Act, namely, to destroy the Voice of America, not directly, but indirectly by emaciating amendments.

If the Voice of America needs improvement, and I am sure it does, we cannot get that improvement by cutting its funds so as to make it inopertive. Let us rather give it more strength by reorganizing it, weeding out the inefficient, and by this Congress making a firm declaration of our objectives and policies insofar as the future of the iron-curtain countries is concerned.[10]

State Department staffers in charge of public relations responded this kind of criticism by pointing to some of VOA’s few programs about events behind the iron curtain based in part on information gleaned from monitoring communist broadcasts. At the same time, in their attempt to appeal to conservative lawmakers approving VOA’s budgets, they also highlighted VOA religious programs, even though in reality these broadcasts were also not particularly frequent or lengthy.

The 1951 VOA Program Schedule for VOA English shortwave radio service to Europe and the Middle East showed a remarkably high proportion of music programs of various genres, including “Symphony Orchestra,” “Opera Concert” and a 15-minute “Jam Session” (jazz). The Voice of America “Jazz Hour” hosted by Willis Conover which later became popular in the Soviet Union in other Soviet block countries did not start until January 1955.

The 1951 VOA program Schedules brochure was free of almost any political content. An article on the history of religious radio broadcasting had references to freedom of religion in the United States but no information or comments on any persecution of religion in communist countries.

Overall, the Voice of America brochure reflected the blandness of most of VOA’s programming at that time and the temperament of State Department diplomats in charge of VOA. In addition to the article on religious radio broadcasts in the U.S., the 1951 brochure had two small articles about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, an article on presidential radio addresses, another article on the future of radio and television, a profile of Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Congressman John Kee (D-WV), and a feature on John Peirce, an American “Painter of Family Life.”

While it was not political propaganda per se against any particular country or regime, some of the articles in the 1951 VOA brochure could be perceived by more discerning readers as rather unsophisticated propaganda in favor of democracy. That is about as close as the Voice of America came to countering Soviet propaganda in 1951, but due to pressure from Congress and American public opinion, as well as competition from newly-established Radio Free Europe, changes in VOA programming were already being made and would be fully implemented later in the 1950s.

GEORGE WASHINGTON

GEORGE WASHINGTON whose birthday is celebrated as a national holiday in the United States, personified the strength and dignity apparent in Gutzon Borglum’s monumental sculpture at Mount Rushmore. Carved to commemorate his contributions to American history, Washington’s portrait measures eighteen meters from chin to forehead, about twice the size of the head of Egypt’s Great Sphinx.

Washington lived between 1732 and 1799 and served his country as a soldier and statesman. He led the Continental Army to victory in the struggle for American independence. As the unanimous choice of the new Republic’s citizens, he became the first president of the United States.

Although revered as a military hero, Washington attained his greatest fame as a statesman. His dynamic leadership and devotion to the democratic cause inspired his countrymen to launch the new nation on its course.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

DURING the month of February, in accordance with its annual custom. THE VOICE OF AMERICA will broadcast programs commemorating the birthdays of two eminent presidents of the United States: Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, and George Washington, Father of His Country. Lincoln’s birthday is observed on February 12th and Washington’s on February 22nd.

The subject of more biographies than any other American, Abraham Lincoln rose to the leadership of his country from humble beginnings. Lincoln’s life exemplifies the inherent birthright of every citizen to attain the nation‘s highest honors.

The rugged yet gentle face of Abraham Lincoln reveals the humanitarian qualities which Gutzon Borglum has reproduced in the huge sculpture carved on the dome of Mount Rushmore, in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

| 1. | ↑ | 97 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 97, Part 7 (July 23, 1951 to August 13, 1951); July 24, 1951; p 8752. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 3. | ↑ | Blane, Arthur Bliss. I Saw Poland Betrayed. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1948, p. 219. |

| 5. | ↑ | 97 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 97, Part 7 (July 23, 1951 to August 13, 1951); July 24, 1951; pp. 8749-8750. |

| 7. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 8752. |

| 9. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 8782. |

No comments:

Post a Comment