Debak Das, South Asian Voices, May 29, 2019

The Kargil [JB - see] war marked a significant shift for Indian diplomacy at both the domestic and international levels. By the third week of May 1999, it was clear that India would have to engage in military operations to clear the infiltrators from the Indian side of the Line of Control (LoC). The challenge was to do this in a manner that saw India remain legitimate and gain support from both the domestic and international audience. India’s success in the Kargil war was a result of its successful combination of diplomacy and the use of force.

At the domestic level the Indian government, particularly the military, engaged in public diplomacy [JB emphasis] embracing the TV with the aim of controlling the narrative and rallying citizens together. At the international level, India sought to ensure that it was seen as a victim of Pakistan’s aggression and was acting purely in self-defense. More importantly, in the aftermath of the 1998 tests, India sought to ensure that it did not lose further standing in the international community. While India achieved considerable successes in both these endeavors, twenty years on, some of these lessons from these successes may have been forgotten as India backslides into ad hoc public and international crisis diplomacy.

Public Diplomacy

Kargil was India’s first television war. For the first time on Indian television, journalists reported from the frontline and images from the war saturated TV screens. This rallied public opinion in favor of Indian action. Among other things, this manifested in blood donations to the Indian Red Cross Society in New Delhi—which tripled during the war. Additionally, donations to soldiers’ welfare funds increased exponentially—while movie stars and cricketers did this publicly, school children across the country collected money to donate to these funds. Images of wounded soldiers, coffins, and bereaved families created awareness and solidarity. Furthermore, the use of the media was seen as a “force multiplier” for the Indian armed forces—it boosted morale of Indian soldiers in the frontlines.1

The Indian government aimed to capitalize on this dynamic by engaging with the media more and controlling the information in circulation to its advantage. To this end, routine media briefings by the Ministry of Defense were upgraded by the end of May to daily briefings conducted jointly by Indian Army, Air Force, and Ministry of External Affairs spokespersons.2 However, this was an ad hoc arrangement and not an institutionalized one.

Pakistan was enabled to portray Indian censorship as “fear of the truth”—an ill-considered policy that cast India in negative light.

Despite the ostensible success of Indian government in managing the narrative during the Kargil war, there were some shortcomings. The Kargil Review Committee Report (chaired by K. Subrahmanyam) stated that with regard to information policy and media relations, India did “fairly well in some respects, but not well enough.”3 The report highlighted that there was no media cell to assist reporters and that few of the journalists at the front had any training in war reporting.4Furthermore, the report criticized the Indian ban on cable operators showing Pakistani TV and access to the Dawn newspaper’s website on the internet. This enabled the Pakistan to portray Indian censorship as “fear of the ‘truth’”—an ill-considered policy that cast India in negative light.5 Ultimately, even though India successfully made use of public diplomacy at this scale for the first time in 1999, there remained critical issues to be addressed and the Kargil Review Committee rightly pointed that out. However, two decades on, it is not clear if these lessons were learnt by the Indian government.

International Diplomacy

India’s biggest success during the Kargil war was in the realm of international diplomacy. In the aftermath of the 1998 nuclear tests India was under sanctions—the UN security council resolution 1172 had condemned its actions, and multilateral and bilateral sanctions had India on the back foot when 1999 came around. It was in this context that India decided to not cross the Line of Control (LoC). It needed international opinion to be in its favor—much like the support of the domestic audience, the support of the international community was seen to be a potential “major force multiplier.”6

As General V.P. Malik highlights in his book India’s Military Conflicts and Diplomacy, India’s goals with regard to the international community were:

- To convince the world that India was a victim of Pakistan’s aggression—the latter had violated the Simla Agreement.

- Demonstrate that the infiltrators were not militants but Pakistani Army regulars.

- Demonstrate ‘responsibility and restraint’ as a nuclear power that had recently caused a setback to the nuclear non-proliferation regime.7

These goals were achieved by the Indian diplomatic corps and enabled by India’s restraint from crossing the LoC. By the end of June, the U.S. government, the European Union, and the G-8 all threatened sanctions on Pakistan if it did not withdraw to its side of the LoC.8 International pressure was building up. Even Pakistan’s traditional allies in the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) chose to water down its resolutions against India. When Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif went to Washington, D.C. to meet President Bill Clinton on July 4, 1999, there was no international ally for Pakistan to turn to. As General Pervez Musharraf later admitted in his book In the Line of Fire, India’s efforts to isolate Pakistan diplomatically had worked and created a “demoralizing effect on Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.”9 Sharif would eventually cave to Clinton’s pressure thus bringing the war to an end. Until the end of the negotiations, the U.S. State Department kept the Indian government in the loop—marking a shift from earlier India-U.S. relations during India-Pakistan conflicts.10 Indian military successes in Kargil notwithstanding, Indian diplomacy scored a clear win during this conflict.

Legacy

The legacy of the success of Indian diplomacy during Kargil is mixed. The main legacy of Indian diplomacy is the positive turn in Indo-U.S. relations. The Kargil war marked the first instance in the history of South Asian conflicts that the United States strongly supported India. It lay the foundation of the current United States-India relationship by leading to the Strobe Talbott-Jaswant Singh talks that eventually culminated in the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal almost a decade later. Furthermore, in subsequent conflicts too, India was able to bear international pressure down on Pakistan—particularly in the aftermath of the 2001 Parliament attacks and the 2008 Mumbai attacks. This was a legacy of diplomatic precedent set during Kargil.

The Kargil war marked the first instance in the history of South Asian conflicts that the United States strongly supported India.

On the flip side however, there was no institutionalization of the process. The shift towards the use of ad hoc force instead of diplomatic means in recent conflicts with Pakistan demonstrate the lack of permanence of the lessons of Kargil. This is particularly evident in the context of public diplomacy. In subsequent crises—the most recent one after the Pulwama terror attack—the Indian government and armed forces appeared to be scattered and unable to produce a coherent and transparent narrative for public and international consumption. This is a far cry from the successful public diplomacy during the Kargil war. The Kargil Review Committee Report’s suggestion of a media cell to assist reporters with packets of information and coordinate crisis reporting was not taken up, leading to ad hoc uninstitutionalized nature of public information dissemination.

Twenty years later after Kargil, India needs to revisit the finer points of its diplomatic successes at both the domestic and international level. The main lesson for strategists from 1999 is that the effective use of force must be accompanied by diplomacy to attain concrete political goals. Given the low ebb in the relations between India and Pakistan at the moment—coupled with greater Indian willingness to use force—it is important for the Indian government to learn from Kargil, and lay out specific political goals and use diplomatic means to attain them. This needs to be in the form of an institutionalized agenda to put diplomacy first and the ad hoc show of strength second.

Twenty years later after Kargil, India needs to revisit the finer points of its diplomatic successes at both the domestic and international level. The main lesson for strategists from 1999 is that the effective use of force must be accompanied by diplomacy to attain concrete political goals. Given the low ebb in the relations between India and Pakistan at the moment—coupled with greater Indian willingness to use force—it is important for the Indian government to learn from Kargil, and lay out specific political goals and use diplomatic means to attain them. This needs to be in the form of an institutionalized agenda to put diplomacy first and the ad hoc show of strength second.

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an SAV series on the enduring debates and legacies of the Kargil conflict twenty years later. Read the series here.

Image 1: Guarav Chaturvedi via Flickr

Image 2: The India Today Group via Getty

***

- Satish Chandra Tyagi, The Fourth Estate: A Force Multiplier for the Indian Army, (with the Specific Backdrop of Kargil Battle) (New Delhi: Gyan Pub. House, 2005), 21.

- Kargil Review Committee, From Surprise to Reckoning: The Kargil Review Committee Report, New Delhi, December 15, 1999 (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2000), 216.

- Kargil Review Committee, 215.

- Kargil Review Committee, 215.

- Kargil Review Committee, 218.

- V. P Malik, India’s Military Conflicts and Diplomacy: An inside View of Decision Making (Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013), 127.

- Malik, 127.

- Lowell Dittmer, South Asia’s Nuclear Security Dilemma: India, Pakistan, and China (Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), 145.

- Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire: A Memoir(New York: Free Press, 2006), 93.

- Bruce Riedel, “American Diplomacy and the 1999 Kargil Summit at Blair House,” Policy Paper Series (Center for the Advanced Study of India, University of Pennsylvania, 2002).

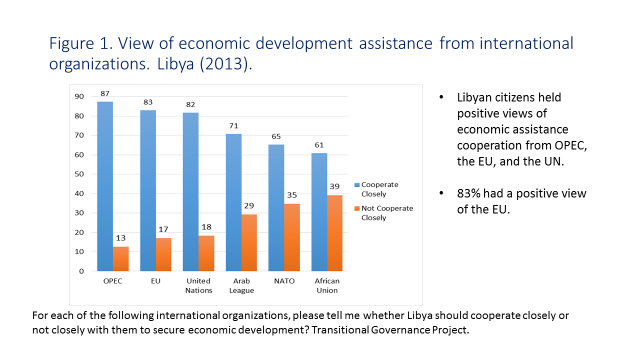

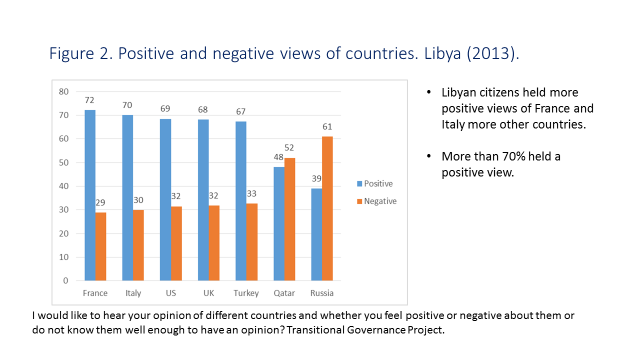

Libyans saw other regional organizations, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in a less positive light. Seventy-one percent regarded the Arab League in positive terms, compared to 65 percent for NATO and 61 percent for the African Union. The latter is perhaps not surprising, given that NATO had recently intervened in Libya’s civil war by enforcing a no-fly zone. The US-led NATO intervention in Libya was welcomed by many Libyans at the time, though certainly not by all. This was reflective of the early optimism both among Libyans as well as internationally about the prospects for transition to democracy. As of 2013, 81 percent of Libyans were optimistic or very optimistic about the future of their country,

Libyans saw other regional organizations, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in a less positive light. Seventy-one percent regarded the Arab League in positive terms, compared to 65 percent for NATO and 61 percent for the African Union. The latter is perhaps not surprising, given that NATO had recently intervened in Libya’s civil war by enforcing a no-fly zone. The US-led NATO intervention in Libya was welcomed by many Libyans at the time, though certainly not by all. This was reflective of the early optimism both among Libyans as well as internationally about the prospects for transition to democracy. As of 2013, 81 percent of Libyans were optimistic or very optimistic about the future of their country,

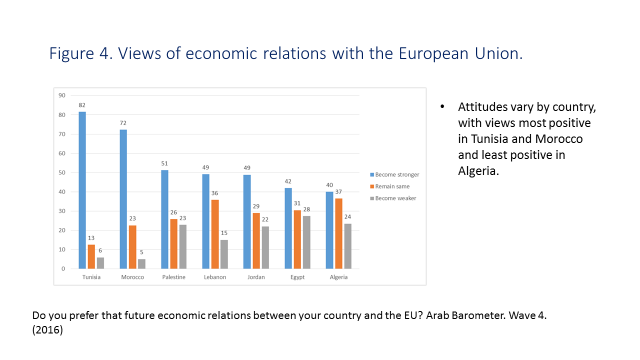

Yet attitudes across the seven Arab countries varied dramatically (Figure 4). The most favorable views of the EU were in Morocco and Tunisia, while the least favorable were in Algeria, which was colonized by France for 130 years. Fully 82 percent of Tunisians and 72 percent of Moroccans desired stronger ties with the EU while about half of all Palestinians, Lebanese, and Jordanians did. Only 42 percent of Egyptians and 40 percent of Algerians would like to see stronger economic ties with Europe.

Yet attitudes across the seven Arab countries varied dramatically (Figure 4). The most favorable views of the EU were in Morocco and Tunisia, while the least favorable were in Algeria, which was colonized by France for 130 years. Fully 82 percent of Tunisians and 72 percent of Moroccans desired stronger ties with the EU while about half of all Palestinians, Lebanese, and Jordanians did. Only 42 percent of Egyptians and 40 percent of Algerians would like to see stronger economic ties with Europe. The positive views that Tunisians hold toward Europe are striking given that Europe, and France in particular, supported the Ben ‘Ali regime. But European countries have generally had strong productive relationships of trade and tourism and no European country has generally directly intervened in either country since their independence from France.

The positive views that Tunisians hold toward Europe are striking given that Europe, and France in particular, supported the Ben ‘Ali regime. But European countries have generally had strong productive relationships of trade and tourism and no European country has generally directly intervened in either country since their independence from France.