Nick Kolakowski, fastcompany.com, 09.06.18; via; article contains additional photographs by its author

***

[JB -- I can't help but express my reservations about this fine, honest article's closing paragraphs, unless the author was writing ironically: "FROM CLARITY TO CHAOS [:] But if any one thing will doom public diplomacy, it’s the simple fact that the war for hearts and minds is fought today on social media. ... you need a couple of kids who are really, really good at creating memes that can rocket across the entirety of Twitter or Facebook within a matter of hours. And the goal of this new game isn’t to offer clarity (or your version of clarity, at least); it’s chaos and discord."]

***

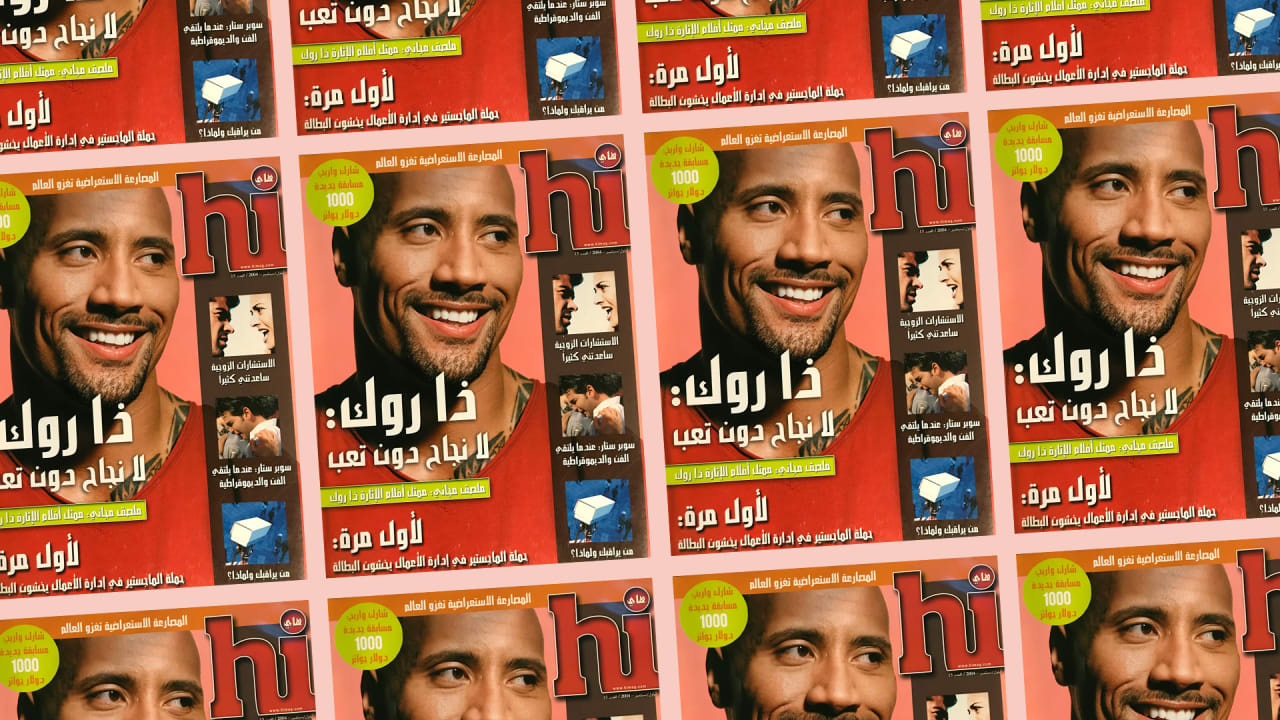

author's image [one of many visually interesting items] from his article

In 2003, I was part of an ill-fated effort to charm the Middle East with a government-funded magazine. It can teach us about propaganda in the Trump era.

In 2003, you could’ve made a good argument that relations between the United States and the Middle East had never been lower. The U.S. military was embroiled in ongoing conflicts with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda elements in Afghanistan. The Guantanamo Bay detention camp was a year old, and treatment of its detainees attracted international condemnation.

And, of course, that was the year the U.S. military invaded Iraq.

But even as the first tanks rolled into Baghdad, the U.S. State Department was already trying to win hearts and minds in the region, not through brute force but with glossy propaganda—specifically, a government-funded monthly magazine called Hi that featured celebrity interviews and articles on American culture. Published in Arabic, the magazine followed in the footsteps of similar U.S. government efforts, such as Radio Free Europe, which began as a news broadcast over the Iron Curtain.

I worked as an editor for Hi. It was my first job out of college, and as such things go, it was exciting. But it was also a complete and utter failure, both as a media venture and an engine for propaganda. I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately, because Trump and his administration have been rejiggering our diplomatic approach to other countries, and it seems we’ve now largely abandoned attempts at cultural outreach. Hi was supposed to give people from Cairo to Kuwait City a deeper understanding of the United States, and then—at least in theory—something good would happen.

But that “something good” was never clearly defined throughout the magazine’s lifespan, despite its eventual expansion to 18 countries at an annual cost of $4.5 million. And so it folded after two and a half years. In its doom, we see echoes of issues that still plague U.S. diplomacy in the age of Trump: a lack of direction from the very top, a systemic inability to articulate an endgame—and a willingness to implode in the face of online fury. Contrast this with the Cold War, when the United States could boast of considerable successes in public diplomacy [JB emphasis] and information warfare, as well as project a coherent image to the world.

At the beginning, the State Department had high hopes for the Hi magazine project. The idea was to make something glossy and fun that would “explain” America to a younger demographic across the Middle East. “I think when you are trying to reach out and have a dialogue with, particularly young people, you need to think about the areas that they’re interested in talking about,” Philip Reeker, a State Department spokesperson, said during a media gathering in August 2003. “And so perhaps targeting that audience with a dense and comprehensive foreign policy journal is not going to be a best-seller on the newsstands.”

The State Department farmed out Hi magazine’s production to the most competitive bidder: The Magazine Group, a Washington, D.C., custom publisher, which had me report to two people from whom I would learn quite a bit: Randall Lane, who would later become the editor of Forbes, and Fadeel al-Ameen, who, in addition to wrestling with the State Department on a daily basis, oversaw the translation of the American writers’ work into Arabic. We had a roomful of Arabic-speaking translators, in addition to a stable of freelancers roving the country’s highways and byways.

When you’re trying to cover something as big and diverse as “America,” you find yourself in a lot of odd places. One month, I was dispatched to cover Native American reservations and casinos in Oklahoma (trip highlight: almost driving into a brush fire). On my next assignment, I was “embedded” with World Wrestling Entertainment for a show in Rockford, Illinois (trip highlight: watching Dave Bautista, still years away from movie fame, pile-driving people into the mat). I wrote about scientists who believed that a human could live to 200 years old, “rock crawlers” who built massive vehicles that could scramble over hills of boulders, and Arab-American congressional staffers.

But there was one thing we were prohibited from writing about—a third rail that, in the eyes of our State Department funders, would have instantly fricasseed the whole enterprise: American foreign policy. Even as U.S. troops battled insurgents in the streets of Fallujah and Ramadi, we couldn’t even hint at the machinations that had brought us to Iraq. Nor the U.S. government’s position on Israel. We could never mention the “War on Terror,” despite its visceral impact on our readership.

Domestic politics were another high-voltage no-go zone. In his book The Zeroes, which mostly deals with his experiences in the luxury magazine industry in the years before the Great Recession, Lane mentions one Hi-related meeting at the State Department in which an innocuous photograph of hikers and pack mules became political football. Pointing to the mule, a high-level official said: “This has to go… too pro-Democrat.”

Ironically, it was domestic politics that eventually doomed the whole endeavor, although not in the way any of us expected. As Hi began to attract attention in the American press, partisan publications fired broadsides from both sides of the aisle. One cannonball came from the American Prospect, known for its liberal take, which damned the project as out-of-touch with reality. “The Arab-language monthly Hi magazine, produced since 2003 for the State Department, has pitched America as a gee-whiz futuristic society whose consumers are obsessed with the latest gadgets and peculiar dating strategies,” wrote senior editor Garance Franke-Ruta. “No joke: Hi magazine recently featured a story on the ‘Dinner in the Dark’ dating service, and another on Flexcars, whose relevance to, say, tribal areas of Pakistan is open to some serious question.”

At nearly the same time, Little Green Footballs, a conservative website, nailed a Hi article on metrosexuality, then the latest fad. “You are not going to believe what the U.S. State Department thinks is the best way to promote America’s image to the Arab world: Real men moisturize.” The comments on the article suggested a deep vein of collective anger that tax dollars were being spent on such endeavors. (“What the hell? Someone send the Los Alamos goons to beat some sense into the State Department, please,” wrote one commenter—and that was one of the nicer ones.)

It got worse: U.S. News and World Report grabbed onto the metrosexual angle, and the State Department had us yank that story from the website—the best anyone could do, as glossy copies of the issue were already in mid-distribution across the Middle East, from Tunisia to the Gaza Strip to Yemen. As I wrote to a friend at the time: “This brings our tally of People-Who-Hate-Us to: The Conservative Right, the Liberal Left, and Al-Qaeda. The people who like us? Conservative Islamic imams who appreciate that we don’t have pictures of half-clad women on the cover, and my mom.”

Actually, nobody seemed quite sure how many people were reading Hi, despite a stated distribution of 55,000 copies per month. Within the State Department, the combination of bad publicity and internal political pressures eventually squeezed out any desire to keep the project going, and the print magazine was shut down (with a curt press release) in December 2005.

Personally, I wasn’t that distraught over the decision. As the Iraq War continued its merciless grind, it was clear that our efforts weren’t having a substantial impact. Our translators drifted to other jobs; our government minders disappeared into the beige bowels of State Department headquarters; our writers moved onto other magazine gigs. In little over a year, I would be writing for a magazine that focused on Wall Street traders—another arena that would descend into chaos before the decade was out.

SOFT POWER

In 1948, Congress passed the U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Act, also known as the Smith-Mundt Act. It authorized the U.S. government to engage in public diplomacy. The original version of the legislation prohibited the distribution of any government-funded propaganda materials within the U.S., although a 2012 update to the act removed that restriction. As the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in various modes of conflict all over the world, the federal government spent significant amounts of money on initiatives designed to promote the image of the United States abroad. Some of these projects were unconventional, to say the least. For example, the CIA funded Encounter, a prestigious literary magazine that published poetry and essays by luminaries such as Philip Larkin, Clive James, and Kingsley Amis.

Other initiatives had wider reach. There was the aforementioned Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberty, which projected news into Central Europe and the Soviet Union, including reports of protests and riots that communist authorities tried to squelch. (Those outlets continue to broadcast today.) There was also Voice of America, a radio and TV station run by the Broadcasting Board of Governors, which began in 1942 as a means of pushing back against Nazi propaganda; it shifted to focus on the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and continues to produce hundreds of hours of programming every week.

Post-9/11, however, the efficacy of public diplomacy seemed to fade [JB -- see.] Radio Sawa, introduced in 2002 as a replacement for Voice of America’s Middle Eastern service, “failed to present America to its audience,” according to an internal review. Al-Hurra, a government-funded television network aimed at the region, ran into conflicts with Congress over audience sampling and documentation. Over the past 15 years, Voice of America has seen cuts to its budget and programming. And of course, there was Hi, doomed despite the best intentions on its creators’ part.

As the 21st century progresses, U.S. influence abroad continues to weaken. The USC Center on Public Diplomacy, in conjunction with Portland Communications, recently issued its latest global ranking of international soft power. Although the United States ranked first on the groups’ 2016 list, it has now fallen to fourth, behind (in descending order) the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. The study points to a perceived weakening in U.S. diplomatic capabilities as a key reason behind this tumble.

Part of this trend is perhaps due to the changing nature of information. Fifty years ago, those involved in public diplomacy efforts had relatively few competitors, and citizens on the other side of the Iron Curtain were starved for any kind of information that wasn’t Soviet propaganda. By the turn of the 21st century, the State Department and other agencies had to push against the internet, with its exponentially multiplying sites and forums, along with a galaxy of television and radio channels—an impossible task. Across the Middle East, potential readers turned away from Hi and to their web browsers if they wanted information, and not even a cover story featuring Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson was going to change that dynamic.

In the Trump era, things have become even more fragmented and hyperpartisan. While Hi was ripped apart by a few forums and foreign-policy journals, an organ of public diplomacy today might face the wrath of Reddit, 4chan, Infowars, and much more. President Trump’s perpetual war-cry of “Fake News!” makes it that much harder for any outlet (government-funded or not) to assume credibility and legitimacy, especially as autocrats around the world embrace those words in order to undermine criticism. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad recently complained that “we are living in a fake-news era,” and, in Burma, government officials have used the term “fake news” to dismiss reports of internal atrocities.

Whereas the government was once relatively consistent at presenting a united viewpoint, its messaging has become incoherent on key issues. President Trump will push an idea via his Twitter feed—which, ironically enough, has become a powerful tool of public diplomacy—and the agencies beneath him will sometimes push back, or offer an alternative view, as with the recent debate over Russia’s election interference.

FROM CLARITY TO CHAOS

But if any one thing will doom public diplomacy, it’s the simple fact that the war for hearts and minds is fought today on social media. You don’t need a staff of a dozen journalists prepping a glossy magazine, or a hundred-strong crew working at a television or radio station; you need a couple of kids who are really, really good at creating memes that can rocket across the entirety of Twitter or Facebook within a matter of hours.

And the goal of this new game isn’t to offer clarity (or your version of clarity, at least); it’s chaos and discord. Look at how effectively Russia was able to co-opt these platforms to set groups of Americans against one another, assisted unknowingly by domestic hyper-partisans only too happy to Like and Share to their friends and followers.

Facebook and Twitter recently shut down hundreds of fake accounts linked to Russia and Iran, hinting that the 2016 election wasn’t some kind of anomaly; the use of social media to spread political misinformation will continue for the foreseeable future. Although tech companies are scrambling to thwart these attempts, it remains to be seen what they can actually accomplish against opponents who have the motive, funding, and ingenuity to adapt.

During the Cold War, the U.S. government recognized that it was embroiled in a war of ideas with an ideological opponent. Public diplomacy helped it win that war. Then came the “War on Terror,” and the State Department ran roughly the same playbook, only to achieve middling results. Now we’ve entered a new kind of conflict, and the idea of magazines and radio seems rather quaint, in comparison to the reach and power of the modern web; to win the next propaganda war, we won’t need editors—but we might need the creators of memes, funny posts, and YouTube videos.

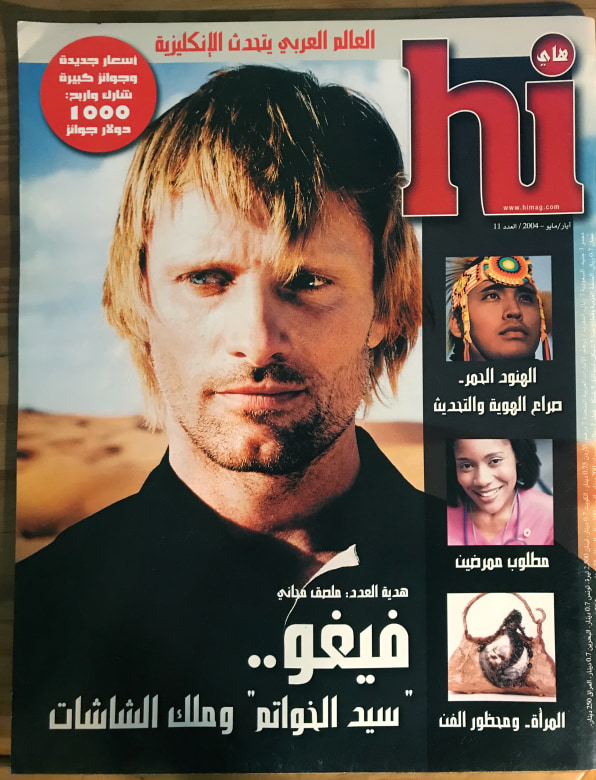

author's image [one of many visually interesting items] from his article

No comments:

Post a Comment