digdipblog.com, September 6, 2015

Recent moths [sic - JB] have seen an abundance of articles dealing with Russia’s use of trolls in order to shape online public discourse regarding its foreign policy. According to one article, the Kremlin now manages a troll army used to promote Russia’s stance on numerous issues (e.g., Ukraine, Syrian Civil War, Iran nuclear agreement) and discredit Russia’s opponents. While Russia’s alleged use of trolls warrants further investigation, the topic of this blog deal with Russian official communication on social media, or its digital diplomacy activity.

Framing deals with the manner in which events, issues and actors are portrayed in a communicative text (e.g., newspaper article) so as to promote a certain understanding. Following their migration online, world governments began using SNS such as twitter and Facebook in order to frame issues and events thus promoting their agenda amongst a global public sphere. Framing through SNS (social networking sites) may be of great benefit to governments as they can directly interact with foreign populations and attempt to influence their opinions and gain their support. For instance, the US embassy in Moscow may use its twitter channel to foster dialogue with Russian citizens and promote the US’s framing of events in the Ukraine.

Russia is no stranger to the use of online platforms for framing. In November of 2014, Russia launched the Sputnik News Agency meant to expose a global audience to Russian foreign policy. However, digital environments may be viewed as highly competitive arenas in which numerous actors try to promote their own frames. This is a result of the fact that social media users may follow the Russian foreign ministry, the US State Department, the UK’s embassy in Moscow and a variety of news organizations and citizen journalists or bloggers. A country’s ability to promote its own framing of events and issues therefore rests on its ability to attract large audiences to its social media channels. SNS profiles may also be used in order tolisten to foreign audiences, foster dialogue with them and gauge public opinion.

Currently, Russia’s digital diplomacy efforts, and frames, may be challenged by those promoted by NATO states given rising tensions over the situation in eastern Ukraine. Likewise, Western and Middle Eastern nations may challenge Russia’s stance on the need to end the Syrian civil war through the ousting of Basahr Assad.

In an attempt to evaluate Russia’s ability to promote its framing of events, I analyzed the twitter activity of Russia’s embassies to the US, the UK and Germany. These countries were selected given their leadership role in NATO, the UN and other international forums, the high penetration of SNS in these countries and the fact that they may offer counter-frames and counter-narratives to those promoted by Moscow.

This analysis included an evaluation of the number of followers Russian embassies on twitter attract when compared to other nations in NATO, Europe and the Middle East. Likewise, I evaluated the “following” parameter that is how many SNS users do embassies follow. This parameter offers initial, yet limited, insight to the extent to which Russian embassies listen to foreign populations.

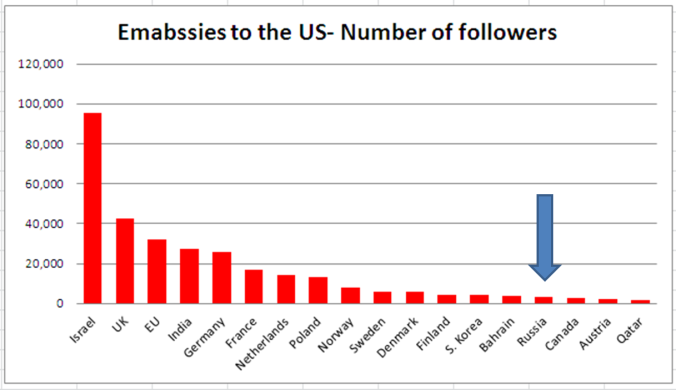

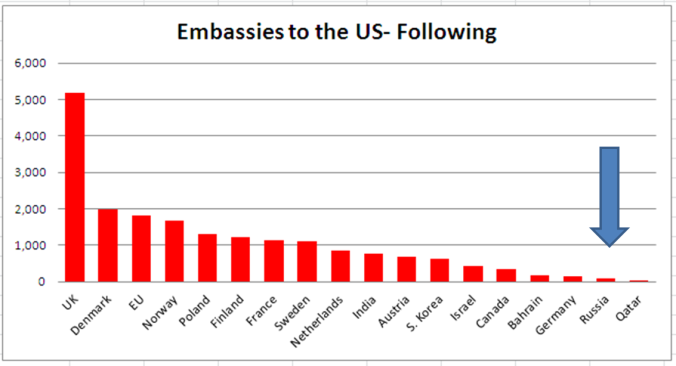

The graphs below include the number of followers, and “following”, of embassies to the US.

As can be seen, Russia’s embassy to the US ranks 15 out of 18 embassies in terms of number of followers. Other embassies (UK, EU, Germany, France, Poland, Norway, Sweden) all attract more followers than Russia. This could suggest that the Russian embassy’s ability to promote its frames amongst American twitter users is limited and that Russia is losing the framing battle to NATO and western countries. With regard to listening to American SNS users, Russia ranked 17 out of 18 indicating a limited ability to gauge US public opinion and shape online content accordingly.

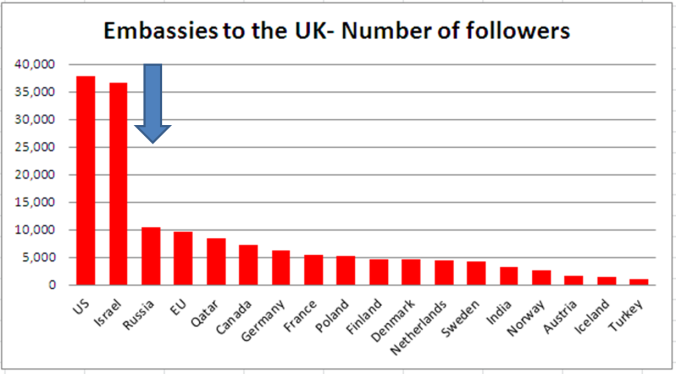

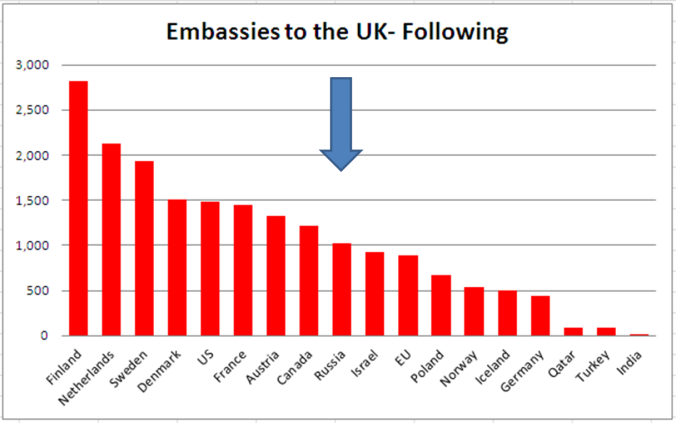

The graphs below include the number of followers, and “following”, of embassies to the UK.

These results are somewhat different than those of the US. Russia ranks 3rd of 18 embassies to the UK in terms of number of followers. While the US ranks 1st, Russia embassy attracts more followers than many European and NATO countries suggesting an ability to promote its frames and compete with counter-frames. However, when evaluating the listening parameter, Russia’s embassy is ranked 9th out of 18 embassies. Such a low score could suggest a lack of ability to tailor SNS content to the public opinion of UK SNS users.

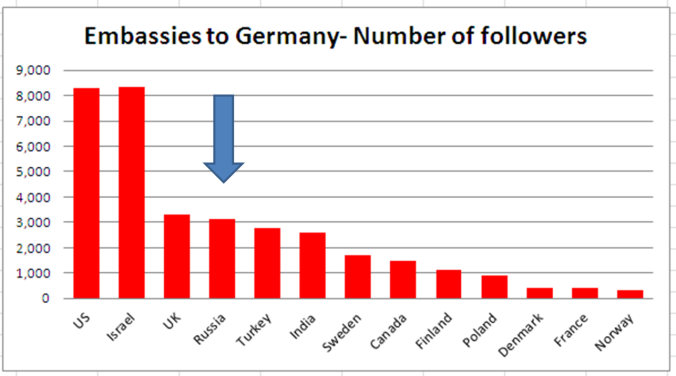

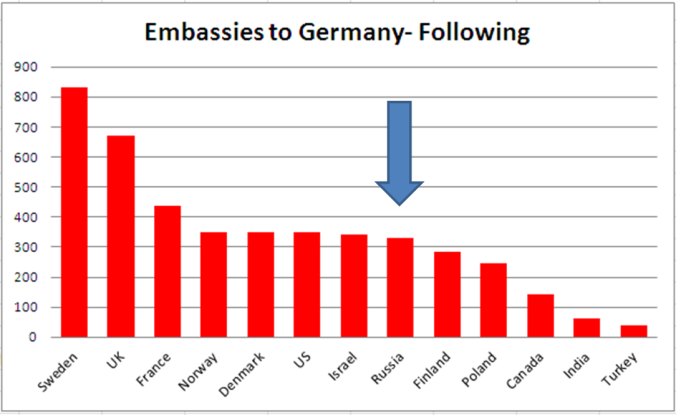

Lastly, the graphs below include the number of followers, and “following”, of embassies to Germany.

In Germany, Russia is ranked 4th out of 13 embassies again coming ahead of European, NATO and Western countries. It should be noted that the sample of embassies to Germany was smaller than that used in the US and the UK given limited use of twitter by foreign embassies in Berlin. As was the case with the US and the UK, Russia’s embassy to Berlin ranks relatively low on the listening parameter.

The results presented thus far could suggest that Russia is able to compete with online adversarial frames, and promote its agenda, among important European audiences. That said, Russia seems to be losing the war over online public opinion in the US and may be lagging behind its adversaries in tailoring digital diplomacy content to the opinions of online audiences.

Finally, I analyzed the number of followers and “following” of Russia’s embassies to the UN in New York and Geneva. While embassies to a foreign nation may attract foreign audiences and foreign press, UN embassies may attract global audiences and the global press and may thus be of great importance to nations’ framing abilities.

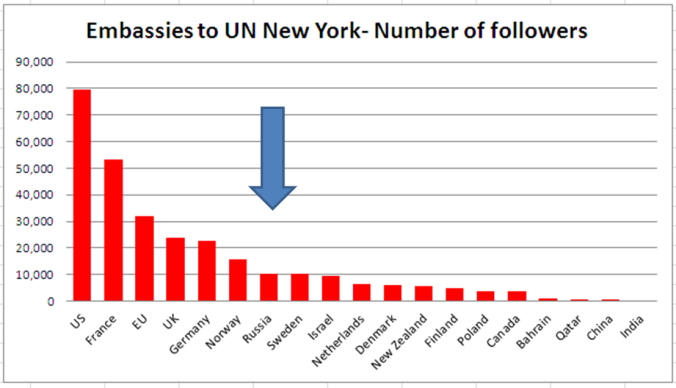

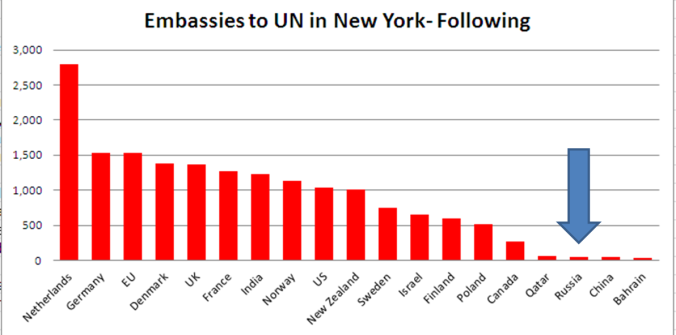

The graphs below include the number of followers, and “following”, of embassies to the UN in New York. (Note that the sample used here was a more global one when compared to that used in the US, UK and German analysis).

As can be seen, Russia’s embassy to the UN in NY is ranked 7th out of 19 embassies lagging behind the US, EU, France, Germany, Norway and the UK. Such a low ranking could suggest that Russia’s “framing adversaries” attract a larger global audience and are thus able to promote their understanding of issues, events and actors. As was the case with European capitals, Russia ranks low on the listening parameter and is ranked 17th out of 19 embassies to the UN.

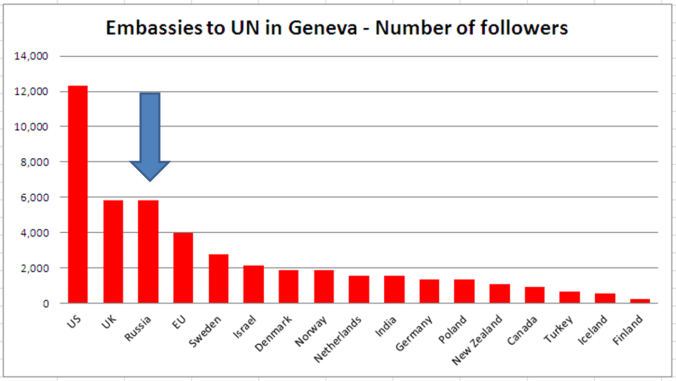

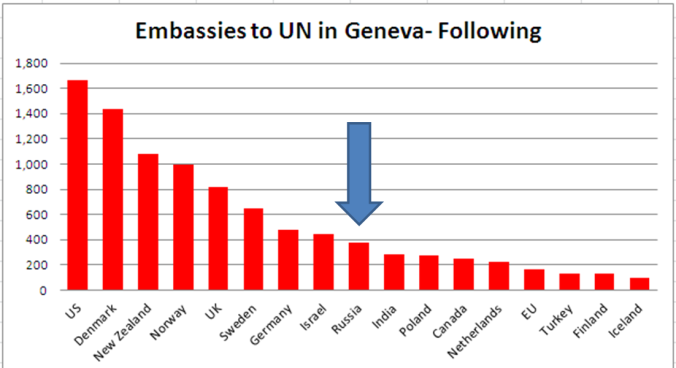

The final two graphs below include the number of followers, and “following”, of embassies to the UN in Geneva.

As can be seen, Russia’s embassy to Geneva is ranked 3rd out of 17 embassies coming ahead of many Western or NATO countries. However, in the “following” parameter it ranks 9th out of 17 embassies.

The results of this analysis do not offer a definitive answer as to Russia’s ability to disseminate its online frames through embassy digital diplomacy channels. As such they are but a mere stepping stone in a greater effort. Yet the results do suggest that Russia’s digital diplomacy efforts prevent it from communicating with important foreign audiences. In the US, arguably one of the most important battle grounds for Russian public diplomacy, Russia lags behind states who offer counter-frames and counter-narratives to that promoted by Moscow. While its embassies in London and Berlin are relatively popular, all three ranked low on the listening parameter. This may suggest that Russia prefers monologue to dialogue and lacks the information necessary to tailor digital diplomacy content to local public opinion, an important finding as tailoring increases the relevance and effectiveness of digital diplomacy content.

The UN analysis offers contradictory results as Russia lags behind many nations in New York but leads in Geneva. Yet in both these arenas, Russia prefers monologue to dialogue. Likewise, in both New York and Geneva Russia’s embassies lag behind the US and the UK whose counter framing may be more effective than Russia’s framing. Thus, Russian digital diplomacy may be losing the battle over online framing and as a result the battle over the ‘hearts and minds’ of a globally connected public sphere.

No comments:

Post a Comment