artsy.net

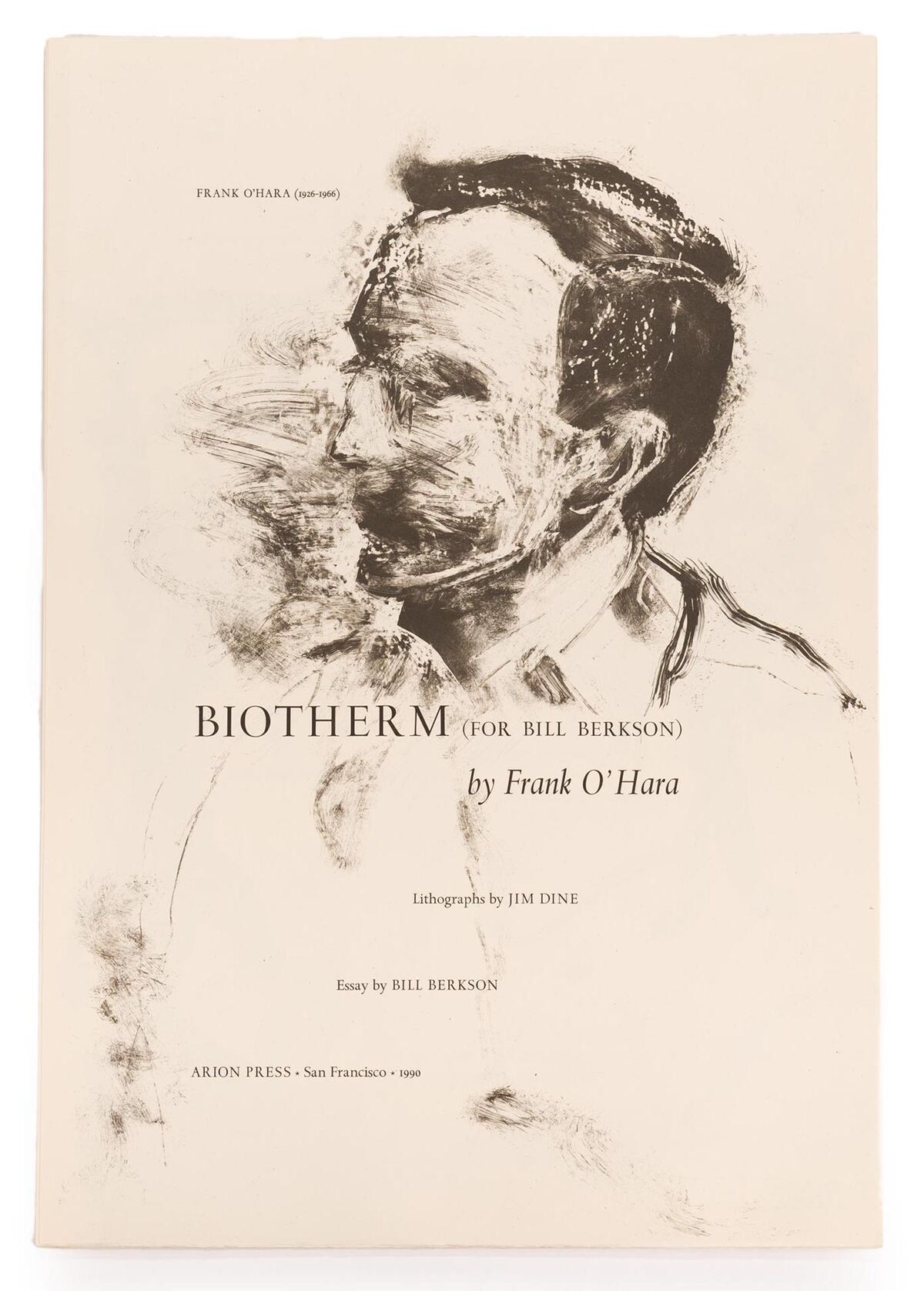

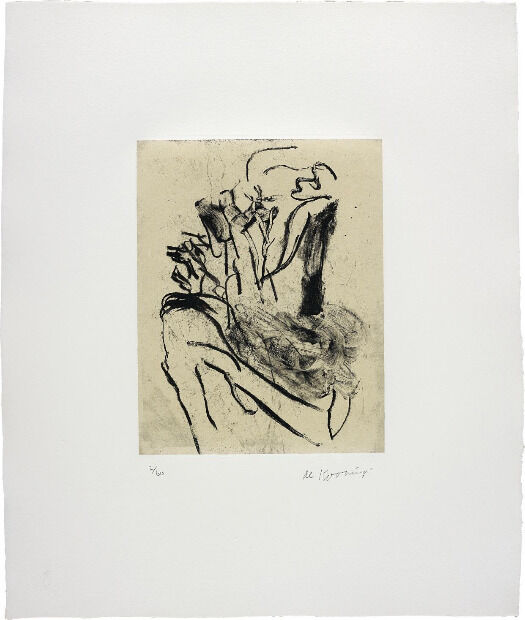

Jim Dine, Biotherm by Frank O'Hara, 1990.

In the history of museum employees, Frank O’Hara wins the prize for taking the most legendary (and productive) lunch breaks. As a curator at the Museum of Modern Art from 1955 to 1966, he used the midday respite to pen his famous Lunch Poems. He vividly rendered his activities in New York, from consuming a hamburger and a malted to spotting cabs and construction workers on the streets. In “Ave Maria,” he famously urged American mothers to let their children go to the movies for sordid reasons. “They may even be grateful to you,” he wrote, “For their first sexual experience / which only cost you a quarter.”

These verses are emblematic of a larger cultural shift, in the late 1950s and early ’60s, toward Pop Art and aesthetics that embraced the everyday. Yet O’Hara was more than a product of his time. As he co-organized 19 MoMA exhibitions, wrote criticism, and embedded himself among painters, the poet made a direct impact on American art. Additionally, his unfettered support for the Abstract Expressionists of his day offers a glimpse into midcentury America’s sexual and international politics.

Born in 1926 in Baltimore, Maryland, O’Hara grew up immersed in music. He studied piano as a child, harboring dreams of playing professionally (eventually, he viewed writing as “playing the typewriter”). After serving in World War II, he attended Harvard. There, he shared a room with the artist Edward Gorey and began publishing poems and stories in The Harvard Advocate. He traveled to and from New York, becoming enamored with the city and its literary and visual art scene. As he later wrote in the book Meditations in an Emergency, “One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes—I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.”

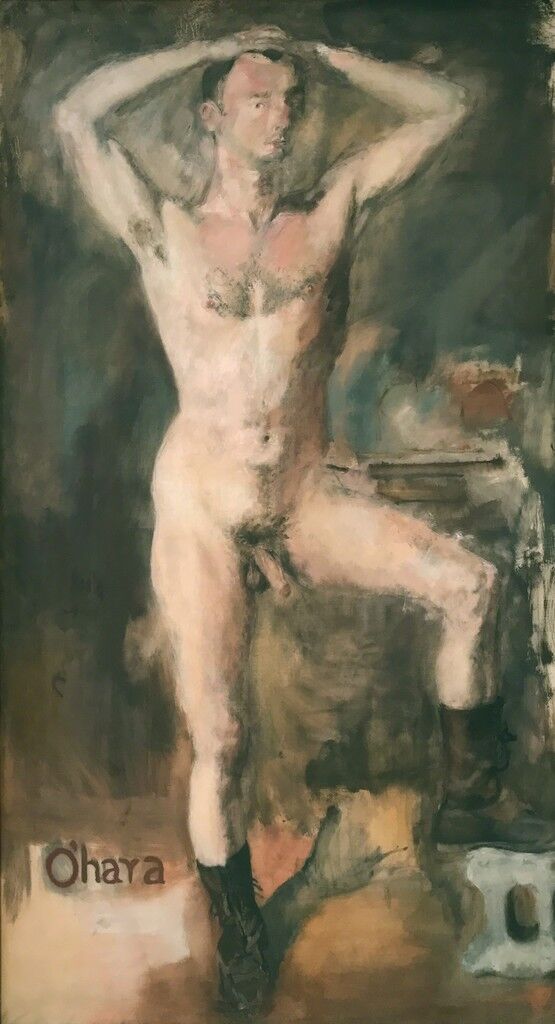

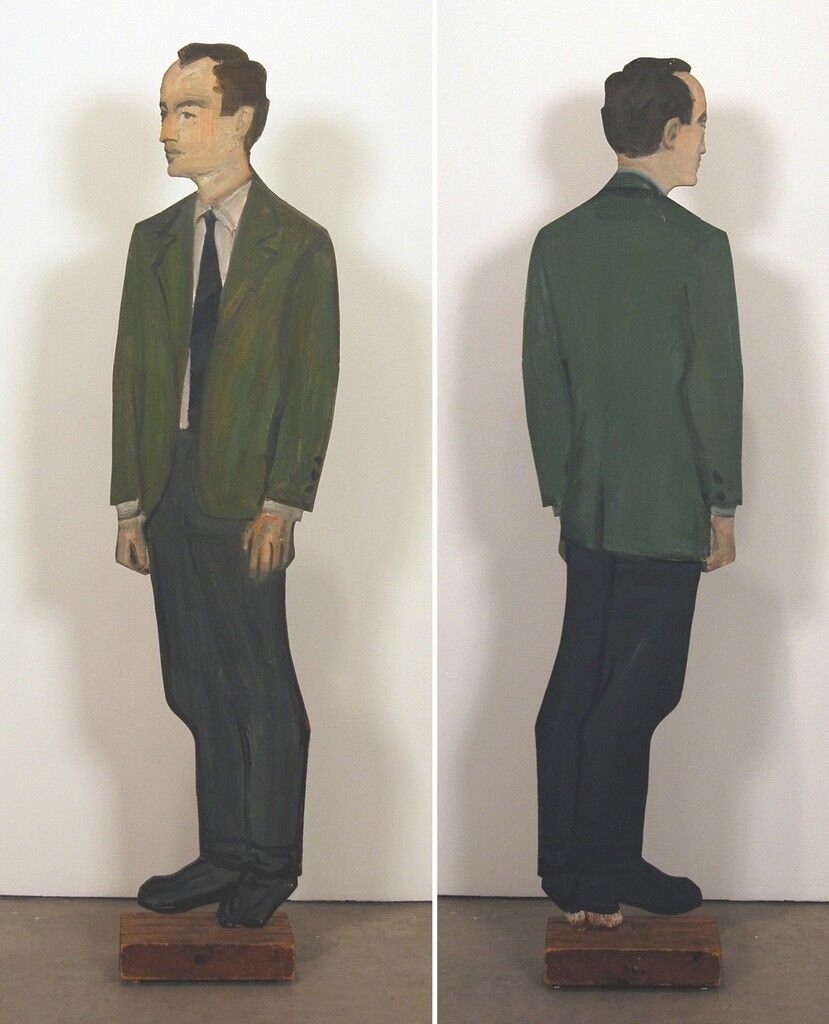

The charismatic O’Hara befriended such New York School poets as Kenneth Koch and James Schuyler, and painters from Willem de Kooning to Jane Freilicher. He so ingratiated himself into the artists’ social circles that, by the end of his life, he was the subject of portraits by major figures, ranging from his lover Larry Rivers to Alice Neel, Elaine de Kooning, and Alex Katz. Jasper Johns titled a dark, brushy abstraction, In Memory of My Feelings(1961), after an O’Hara poem. Indeed, these artist’s diverse styles, from figuration to gestural abstraction, reveal the poet’s widespread influence and the broadness of his social circle.

In 1951, O’Hara got a job at MoMA’s cashier’s desk, selling cards. (According to Andrew Epstein, author of Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry, O’Hara really just wanted to gain free, repeat entry to the museum’s Henri Matisse exhibition.) After a brief hiatus, writing about art and socializing with the right people, he returned to MoMA in 1955 as an assistant curator for the department of painting and sculpture, working his way up to associate curator. Until his untimely 1966 death, O’Hara left an indelible mark on the museum as he helped organize shows of the day’s major Abstract Expressionists (Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline), Surrealists (René Magritte and Yves Tanguy), and more.

In 1958, O’Hara helped curate a majorly influential exhibition, “The New American Painting.” The roster featured 17 artists who’d been crucial to the development of Abstract Expressionism. Work by the era’s heavyweights—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, de Kooning, Kline, Motherwell, et al.—traveled around Europe for a year, beginning in Basel and ending in London with six stops in between. (The show, it should be noted, was hardly comprehensive. For starters, it included exclusively white artists and just one woman: Grace Hartigan.)

O’Hara’s exhibition also functioned as anti-Soviet propaganda. The United States Information Agency, responsible for public diplomacy, helped fund the exhibition. “The New American Painting” suggested that the country’s art was about freedom, strength, and individual—ultimately masculine—gesture, as opposed to figurative Soviet art that promoted Communist propaganda. MoMA’s founding director Alfred H. Barr, Jr., advocated the idea that only totalitarian regimes attacked modern art—a decent argument, of course, if one wants to pre-emptnegative reviews.

Frank O'Hara reading “Having a Coke with You” (1960).

O’Hara championed Pollock in particular, penning the artist’s first monograph in 1959 to accompany a major exhibition at MoMA. Yet the violent, homophobic Pollock had been notably rude to O’Hara, who was openly gay. The poet’s attitude, according to Epstein, ran along the lines of, “Okay, he’s a jerk, but his work’s great.” In an era whose thinkpieces ask “What We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” and “What do we do with art made by bad people?” O’Hara’s approach can seem conservative and even dishonest, albeit common for his time. He dismissed Andy Warhol—apparently “too swish”—a reflection of midcentury queer politics and prejudices. O’Hara could be upfront about his homosexuality, but he didn’t want to be associated with flamboyance. To be fair, however, he did famously revere Lana Turner in “Poem [Lana Turner has collapsed!]”: “I have been to lots of parties / and acted perfectly disgraceful / but I never actually collapsed / oh Lana Turner we love you get up,” he wrote.

O’Hara also wrote influential reviews for ARTnews, characterized by an impressionistic, reverent style. About a Kees van Dongen painting, he wrote, “The women’s eyes are stained with green make-up, their cheeks blush lividly and their bosoms rise and fall as in a revelatory chapter of Proust.” On a Salvador Dalí show: “Less of a Surrealist than before, more the metaphysical dream peddler, the cosmological dandy, the mathematical speculator whose terms are romantic ruins, wood and women.”

O’Hara’s own romantic streak, combined with his enthusiasm for art, are both evident in “Having a Coke with You,” a poem from 1960. “I look / at you and I would rather look at you than all the portraits in the / world,” he writes, “except possibly for the Polish Rider occasionally and anyway it’s / in the Frick / which thank heavens you haven’t gone to yet so we can go / together for the first time.”

“He tended to write about things that he liked with enthusiasm,” affirms Epstein. O’Hara, he says, believed that both bad art and bad poetry would slip into oblivion without his help. If his detractors complained that the reviews were too flowery and devoid of academic rigor, one of today’s most lauded and influential critics, The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl, followed O’Hara’s lead. Indeed, Schjeldahl, too, began his career as a poet, citing O’Hara and John Ashbery as major influences. As critic Roger Kimball once asserted in The New Criterion, “In many respects, Mr. Schjeldahl’s style is a demotic and more dour version of Frank O’Hara’s, the poet-critic upon whom he has most conspicuously modeled himself.”

O’Hara’s early, absurd death contributed to his outsize legacy. In 1966, O’Hara suffered a fatal accident when a dune buggy hit him on Fire Island. His death at age 40 initiated an outpouring of mournful appreciation for the poet. Schjeldahl, who’d fallen in with O’Hara’s set, wrote an obituary for The Village Voice, titled “Frank O’Hara: He Made Things & People Sacred.” A 1993 biography by Brad Gooch, City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara, recounts how after the funeral, painter Philip Guston remarked, “he was our Apollinaire,” comparing O’Hara to the French poet who befriended Picasso and the Surrealists.

Contemporary artists and curators continue to invoke O’Hara’s legend. Sculptor Tom Burr often references O’Hara in his work, going so far as to suggest that one of his sculptures is a stand-in for the man. In 2014, he curated an exhibition at Bortolami with a title derived from O’Hara’s poem “Mayakovsky” (namely the lines “Now I am quietly waiting for / the catastrophe of my personality / to seem beautiful again, / and interesting, and modern”). This March, a satellite exhibition affiliated with the Spring/Break Art Show exhibited only artworks that somehow related to the name (or concept) of “Frank.” It wasn’t complete, of course, without a Larry Rivers portrait of O’Hara.

In 1968, MoMA published In Memory of My Feelings, a book of 30 O’Hara poems accompanied by illustrations by the poet’s artist acquaintances, including Freilicher and Guston. In a review for ARTnews, poet John Ashbery explicitly pronounced his friend’s great influence. “O’Hara’s personality was a subtle but pervasive force on the New York art scene,” he wrote. “If the Museum and the artists who have illustrated this book are what they are today, it is at least partly because O’Hara was one of the first to think they were that.”

Alina Cohen

No comments:

Post a Comment