Matt Novak, paleofuture.gizmodo.com; see (1) (2: "The Man who invented truth" by scholar Nicholas Cull)

“I don’t mind being called a propagandist,” Edward R. Murrow told a reporter at the Miami Herald in April of 1962. “So long as that propaganda is based on the truth.”

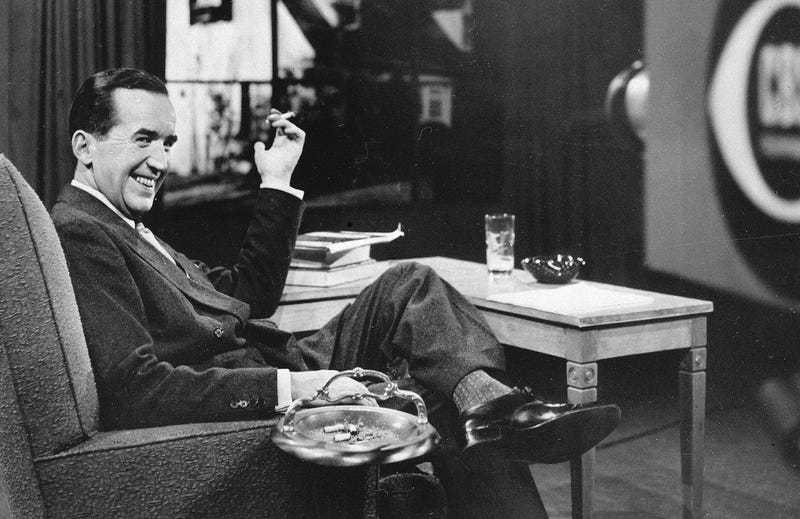

Today, Edward R. Murrow’s name is synonymous with integrity in journalism. He reported from the frontlines during World War II and took on Joe McCarthy’s communist witchhunt in the 1950s. But what’s less well known to Americans today is his role as the country’s leading propagandist in the early 1960s. A new book by Gregory M. Tomlin called Murrow’s Cold War: Public Diplomacy for the Kennedy Administration seeks to remedy that.

The term “propaganda” certainly carries with it a lot of negative connotations to Americans in the 21st century. But the word was used proudly during Murrow’s tenure as the head of the United States Information Agency (USIA) from 1961-1964 to describe government efforts to influence public opinion overseas. The Cold War was in constant danger of becoming hot. And USIA used countless film, TV, radio, and book programs to get out its message that America’s model of democracy and capitalism was superior to the Communist model of socialism and oppression.

The existence of Murrow’s last job (he’d die of lung cancer in 1965) is relatively well known to historians. But his unvarnished legacy as a propagandist remains fuzzy in the public imagination. Films like George Clooney’s Good Night and Good Luck (2005) and the countless journalism awards named for Murrow have helped gloss over his years as an official government mouthpiece. It should be noted that he was as good at his new job of active persuasion as he was at his old one in hard news. And perhaps better.

The United States Information Agency (known overseas as the United States Information Service) was founded in 1953 to conduct propaganda and psychological warfare operations around the world. The USIA wasn’t allowed to produce material for American consumption due to laws against propaganda aimed at Americans. And as such, the agency’s Cold War activities can be a huge blindspot for people in the United States. The USIA office that Murrow would help to define had an important impact on the way that people outside of the US viewed Americans.

Tomlin’s book takes us through Murrow’s earliest years at CBS in the mid-1930s, where he lied about his credentials to secure a job. Murrow made himself five years older on his CV and claimed to have degrees that he didn’t have, including a master’s degree from Stanford University. The irony of the fact that he was lying to get a job where he’d become the living symbol of integrity is lost on no one.

Tomlin then fast-forwards to Murrow’s years as director of the USIA under President Kennedy. We learn about Murrow’s dissatisfaction with the demands of rapidly commercializing TV industry in the late 1950s, and his pivot to public service when he was asked to head the USIA by the Kennedy administration. Interestingly, the USIA was seen as an agency full of left-leaning pinkos, despite its role as the consummate Cold Warrior. Congresspeople who were inclined to see Murrow as just another pinko constantly slashed funding for the agency despite its explicit role as a propaganda arm of the United States.

Tomlin’s new book explores the various fronts of Murrow’s propaganda battle in every medium, from the promotion of TV content on private stations around the world, to the USIA’s very own global radio network, Voice of America (VOA). But one of the most startling revelations goes above and beyond what we think of as typical propaganda or public diplomacy. Murrow offered counsel to the CIA about ways that he thought they should plan to incite insurrection in Cuba (more commonly known as Operation Northwoods) as well as how they would publicize opposition to the Castro regime as if they had nothing to do with it.

In a December 10, 1962 memo from Murrow to the Director of Central Intelligence, the newsman-turned-propagandist was blunt about advocating for sabotage in Cuba. Murrow suggested that US radio programs feature Cuban dissidents encouraging relatively safe ways to gum up the works in the communist government.

“The Cuban audience should be urged to act with care and cautioned against open rebellion,” Murrow wrote. “The program would be based upon work slowdowns, purposeful inefficiency, purposeful waste, and relatively safe forms of sabotage. Specific examples of the activities urged would be putting glass and nails on the highways, leaving water running in public buildings, putting sand in machinery, wasting electricity, taking sick leave from work, damaging sugar stalks during the harvest, etc.”

Murrow explicitly said that these actions should not be attributed to the United States or the USIA. And that’s where modern day readers would probably be shocked to learn that the man from ye olde TV days was working so intimately with the CIA.

“The program would be strictly attributable to the Cuban exiles with no open participation by USIA or other government agencies,” Murrow continued in the memo to the Director of Central Intelligence. “If real results were achieved, the Voice of America [radio network] could report these as evidence of opposition to the Castro regime through interviews with refugees and extracts from letters.”

These and so many other anecdotes about Murrow’s use of media to tell America’s story abroad (often in more benign ways, like the production of documentaries about the Civil Rights movement) makes this book a worthwhile introduction into both the history of the USIA and the latter stages of Murrow’s career.

The one area where the book seems to falter is in speaking plainly about Murrow’s job. Murrow called his work propaganda, and the US government called his work propaganda. But for some reason, this word has been deemed too harsh for consumption here in the year 2016. Tomlin tells readers early on that because of the word’s negative connotations, he’ll be replacing the word with “public diplomacy” throughout the book. This decision gives the text an air of self-censorship.

As just one example from page 81, emphasis mine:

The U.S. government could saturate a foreign country with multiple forms of public diplomacy, but when disseminated by itself, information could not serve as the “magic bullet” to resolve national security challenges.

Saturated with public diplomacy? Such a phrase almost feels like it was created by a computer running find-and-replace. “Saturated with propaganda” not only feels more natural, but it certainly feels more honest.

Overall Tomlin’s book is a solid examination with plenty of interesting stories that I haven’t elaborated on here. As Tomlin notes, in the year 1963 alone, roughly 600 million people around the world watched a USIA-produced documentary every month. This is to say nothing of the thousands of hours of radio broadcasts distributed in almost forty languages.

Americans have very little understanding of the propaganda efforts done in its name during the Cold War through the USIA in close cooperation with the CIA and US military. Not to mention the propaganda efforts still currently being executed since the USIA was dissolved in 1999 and most of its efforts, including Voice of America, were taken up by the State Department.

The full story of the United States Information Agency, with one of America’s most famous newsman at its helm, is worthy of probably ten books. But for now readers will have to settle for just one, Murrow’s Cold War: Public Diplomacy for the Kennedy Administration.

No comments:

Post a Comment