coldwardiplomacy.wordpress.com; see also (1) (2)

image from entry

The Boston Globe: “The Fulbright, History’s Greatest War Surplus Program”

In a 2013 article for The Boston Globe, Sam Lebovic discusses the origins of the Fulbright program, of which most of the American public are unaware. The Fulbright program, created in 1946, has earned a reputation of high value within the scholarly community; to be awarded a Fulbright is to truly distinguish yourself as an intellectual and a scholar. As Lebovic highlights, the prestige of the program reaches even beyond the scholarly community, and since its inception the Fulbright program has supported 320,000 students, scholars, and teachers to either pursue academic and professional goals abroad or to come to the U.S. in pursuit of those goals.

In Lebovic’s article, he focuses on the disconnect between the program’s perceived intentions and the actual intentions in implementing it initially in 1946. As Lebovic states:

…the Fulbright is often seen as among the most civic-minded international programs of the U.S. government – a vast effort to improve mutual understanding between nations and foster the exchange of ideas…But the origins of the Fulbright program suggest it was actually established for quite different reasons—ones that are less heart-warming, but more interesting. Whatever the program became, it was first conceived as a budget-priced megaphone to transmit American ideas to the world, rather than as a genuine international dialogue. The early history of the Fulbright program offers a window into America’s towering self-confidence in its new role as global superpower in the 1940s. That the program’s effects were ultimately more complicated—and that we have come to see it so differently today—suggests both the hubris of that moment and the impossibility of predicting or controlling what international educational exchanges really do for the world.

Lebovic goes on to explain the origins of the program – created after World War II, the program was initially seen by many American policymakers as the perfect way to showcase American life and the American story to foreigners who would come to America on the exchange program. I take some issue with Lebovic’s conclusions, however, as he removes a lot of nuance from his argument.

I can agree with him that the policy atmosphere at the time certainly was not conducive to an exchange program solely for the long-term goal of “mutual understanding.” As Lebovic says, those who supported implementation ultimately believed that

…While foreigners in the United States would absorb American values, Americans abroad would do no such thing, and would instead spread American culture wherever they went.

It is undeniable that some in the Senate invested in the Fulbright program solely on this basis. What Lebovic misses, however, is Senator J. William Fulbright’s original intention. Senator Fulbright was undeniably a committed internationalist. He believed in the power and the necessity of educational exchange for the betterment of our country as well as the international community. While some who supported funding the program may not have believed so, Senator Fulbright truly believed when he pitched the program that its true value and purpose lay in increasing “mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries.” From the perspective of the program’s founder, this certainly was not meant to be a one-way exchange. In fact, at the end of his career, when he was asked what he had sought to achieve with this program, Fulbright stated: “Aw, hell, I just wanted to educate these goddam ignorant Americans!” Clearly, Fulbright understood the necessity both of combatting negative images of Americans internationally, as well as educating the American public who, at the time of the program’s inception, were not typically globally-educated or familiar.

It is true, though, that Fulbright’s idealistic internationalist vision was not enough at the time to sell his program. The U.S. had just gone through a war; the American public was increasingly expressing isolationist views (not atypical after a war). Tensions were growing, however, between the U.S. and the Soviet Union; Fulbright took advantage of the beginnings of this ideological conflict by pitching the program as a “soft weapon” in the war for hearts and minds abroad.

What Lebovic does get right is the unpredictable nature of such exchange programs, and that while it is hard for research to definitively prove the benefits of such programs, much of the anecdotal evidence that exists supports the success of the program. Lebovic also focuses on the fact that these programs can only be as successful as the individual participants:

But to the extent that the program has facilitated the growth of genuine cultural exchange—and there is plenty of anecdotal evidence, at least, that it has—we shouldn’t be too quick to give credit to the foresight of its first, surprisingly parochial administrators. Better to credit the individual scholars, students, and teachers who have traveled overseas with open minds, both to the United States and away from it, and the countless individuals who have welcomed them. They created the Fulbright program as we know it. In a way, that is one testament to the power of educational exchange: It was far easier to create than it is to control.

That’s something Lebovic and I can certainly agree on.

To read Lebovic’s full article for The Boston Globe, click here.

Book Review: The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989, by Nicholas J. Cull

In The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989, author Nicholas J. Cull details the history of public diplomacy and the role that the United States Information Agency (USIA) played in American policymaking during the Cold War. The book details public diplomacy’s beginnings, borne from America’s national security establishment and originally housed in the USIA. Cull argues that after the USIA was abolished in 1999, the United States lost any type of cohesive public diplomacy strategy, and has not regained one since. Cull focuses on the institutional history of the USIA and the concept of public diplomacy, providing a comprehensive and in-depth overview and understanding of the agency in a way that I do not believe has been done previously.

Cull organizes the book in a chronological order, starting just before the birth of the USIA in 1953 and following its many iterations through various presidential administrations. In this way, it seems that Cull seeks to make it easier for the reader to visualize American propaganda alongside concurrent policy decisions. The reader can see how support for public diplomacy programs and propaganda rose and fell during the Cold War years, the ways in which policy priorities and support for these programs affected USIA’s priorities and objectives, and the importance of the USIA during this conflict. This brings up one issue that I had with Cull’s account – Cull often seems to treat the term “public diplomacy” synonymously with the term “propaganda.” While I certainly believe that propaganda falls under the umbrella of public diplomacy, it seems a disservice to the vast scope and the array of other services provided under that same umbrella to treat public diplomacy as if this might be all that it is. Cull rejects any kind of nuanced analysis on the ever-evolving nature of the term, which I found quite disappointing (and honestly, a bit lazy). Cull also seems to totally ignore the fact that the historical context in which public diplomacy is placed can change the way it is treated – thus while during the Cold War, public diplomacy efforts may have focused on aggressive propaganda efforts and psychological warfare, this cannot be said to hold true in every other era. This treatment seems ironic to me, considering he does so well to nuance the USIA’s effectiveness and prioritization of goals according to the historical context in which the agency was acting. Even more interesting, in a review of the book for The Wall Street Journal, Martha Bayles states that

“Nicholas Cull’s comprehensive history of USIA begins by clarifying what is meant by ‘public diplomacy.’ This is a great service, because since 9/11 every committee, think tank, advisory board and broom closet in Washington has published a report on the topic … none cuts through the semantic muddle as deftly as Mr Cull.”

Unfortunately I would have to disagree. While Cull seems to try to “cut through the semantic muddle,” he does a poor job of it by seriously restricting his definition. I think the “semantic muddle” surrounding public diplomacy probably has to do with the fact that it’s a very complex, and at times subjective and idea-driven, concept. To be fair, simply saying “it’s a tough thing to define” seems like a bit of a cop-out as well – perhaps neither of us have fully succeeded here.

Either way, Cull does provide a very thoroughly-researched and useful source on the beginnings of public diplomacy, the use of American propaganda during the Cold War, and the way that these developed over the course of USIA’s history. Cull seems to be appealing to the American policymaking community and the public, asking for a reconsideration of our treatment of public diplomacy in a time where these functions are housed across various agencies. As Cull says, the U.S. Information Agency was originally created to “tell America’s story to the world” by engaging internationally through the mediums of information, broadcasting, culture and exchange programs. The blurb on Cambridge Press’s website for the book claims it is “the first complete archive-based history of the subject,” and it is certainly a valuable resource for anyone looking to understand the history and the beginnings of public diplomacy, as well as the institutional history of the USIA.

For Further Reading:

- Cull, Nicholas J. The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009. Print.

American Propaganda During the Cold War

From the start of the Cold War in 1945 to its end in 1991, ideological and political hostilities between the U.S. and the Soviet Union resulted in the use of subversive techniques to win hearts and minds both domestically and abroad. As said on Man’s Propaganda blog, subsequent propaganda from these countries embodied “a power battle between both nations to sell their respective ideologies to the world.”

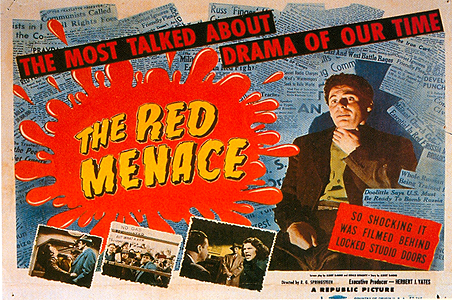

In a post from Man’s Propaganda analyzing the output of American propaganda, the paranoia surrounding the communist threat is palpable. Communism is frequently portrayed as if it were a transmittable disease. Posters and newspaper articles frame Soviet communism in a threatening way, referring to it as “the red menace.” Target audiences for this propaganda included the broader American public, moviegoers, and children. Here are some choice examples of such propaganda, taken from Man’s Propaganda‘s blog post relating to this topic:

“Is this Tomorrow?” A propaganda poster courtesy of the Catechetical Guild Educational Society

“The Red Menace,” a 1949 theatrical poster for the film by director Robert G. Springsteen

“He May Be a Communist,” American Informational Video

As Man’s Propaganda aptly points out, anti-communist propaganda in film, print media, and in schools was meant to manipulate mass opinion, clearly domestically but also internationally. Of course, one of the easiest ways to manipulate an audience is through fear-mongering and presenting a clear and imminent threat in order to other your opposition. The problem, however, is that this kind of ideological messaging often relies on inaccurate stereotypes and can create public paranoias that can quickly spiral out of control (think McCarthyism).

For more on the subject of American Cold War propaganda, and to read it from a more media-based perspective, please visit the source blog at Man’s Propaganda by clicking here.

Huffington Post: “International Student Exchanges Make a World of Difference”

In an older article from The Huffington Post, Stacie Berdan writes about the increase in cultural exchange programs in 2013 – both in the number of exchange students coming to the U.S., and in American students studying abroad. Citing the International Institute of Education’s 2013 Open Doors Report, Berdan uses the report’s statistics to reinforce her argument that international education can help bolster bilateral relationships, not to mention the individual benefits of studying abroad. To share a quote from Berdan’s article, Evan Ryan, then-Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs, said that:

“International education promotes the relationship building and knowledge exchange between people and communities in the United States and around the world that are necessary to solve global challenges. The connections made during international education experiences last a lifetime.”

Such programs, which encourage strong people-to-people connections between nations, are crucial in improving and furthering foreign relationships. Not to mention the invaluable skills that students who study abroad will gain, including increased cultural knowledge, the ability to hold cross-cultural dialogue, knowledge of a foreign language, and a more international, broader outlook and understanding.

Today, I would argue that these programs are at risk of being undercut and undervalued – especially as the American public seems, compared with other nations, to undervalue the importance of studying foreign languages, cultures, and countries. The current presidential administration proposed a 28% budget cut to the Department of State, which funds many of these international educational exchanges. While I doubt this kind of gutting will pass through Congress, it is disheartening to see these functions so devalued and threatened. As Berdan says at the conclusion of her article:

“Through education, we can create greater understanding between the U.S. and every other country in the world. But in order to be successful, Americans must recognize the importance of these relationships and how study abroad can play a significant role. We’ve got a ways to go.”

These words still ring very true today.

You can read Berdan’s article for The Huffington Post here.

Book Review: Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union, by Scott Shane

In Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union, author Scott Shane gives his unique perspective on the collapse of the U.S.S.R. Shane witnessed the collapse of the empire firsthand – he was a journalist in Moscow representing The Baltimore Sun from 1988 to 1991. As Shane describes it, the faults of the Soviet system that had always existed began to widen in these years. While the leadership tried initially to simply reform the system, by 1991 it became clear that reform would not save the Soviet Union. The system, grossly inefficient under central planning and single-party rule, would have to be dismantled. Shane argues that while such inefficiencies were easily masked in the earlier years of the Soviet Union, by the time of its collapse and after the world experienced an information revolution, masking inadequacies was no longer an option for Soviet leadership. Thus, Shane provides a detailed and rich narrative of the fall of the Soviet Empire, arguing that “information slew the totalitarian giant.”

In the early Soviet era, the state had a monopoly on information that was virtually unchallenged. The state leadership was responsible for running the centralized economy in the most efficient and productive manner possible; the secret police was responsible for knowing everything about everyone. The leadership was able to manipulate public information to suit their purposes and to keep people placated. As time passed, however, and as inefficiencies in the system grew while information technology also improved exponentially, the inherent contradictions of the Soviet system would result in its inevitable death. It was Gorbachev who came to power during this final period, and it was Gorbachev who was forced to confront the issue of image vs. reality head-on in an age that made it increasingly difficult to maintain an image contradictory to reality.

Gorbachev chose to pursue policies of glasnost and perestroika, recognizing that if socialism was going to survive, the system would have to change. In a world that was becoming increasingly competitive, the Soviet program of central planning was quickly becoming obsolete. Gorbachev’s vision was that economic restructuring would revitalize the Soviet economy, while increased openness would allow the state to better utilize information. What he did not realize was that once glasnost was implemented, there was no turning back – people were able to see for themselves that the only way to improve living standards was to end communism and allow markets to deliver what consumers wanted rather than what the state mandated.

With the acute perspective of a journalist, Shane describes how the softening of information control revealed to the Soviet people the horrors of Stalinism, the inefficiency and corruption of central planning, and the problems with the Soviet illusion of a “family of nations.” Shane provides evidence of corruption in the Soviet system which runs the gamut from minor details to serious scandal – from the illegal use of Xerox machines by party members, to the “Uzbek Affair,” in which party members made themselves richer by underreporting cotton production, selling the difference on the black market, and pocketing the profits as well as accepting large bribes.

Shane uses the first half of the book to provide the foundations of his argument that the Soviet system was inefficient and largely corrupt. In the second half, he details the forces that ultimately brought on the collapse of communism and the important role that glasnost played in that process. As a result of greater freedom of information, people began to learn the truth about Soviet history, which had previously been modified to fit into party rhetoric. By the 1980’s, television had become the main medium for communist propaganda; after glasnost, new programs were allowed and broadcasters began to cover politics in a different way. Television became a way to expose the lies of corrupt officials; films that had been previously banned were now being aired. As Shane notes here, the Soviet government compulsively kept records on everything; they filmed everything and kept those films locked away, but under glasnost such films became fodder for the growing unrest of the Soviet public. The unintended consequences of glasnost were to paralyze the KGB and to transform the Soviet Union into what Shane calls a “coup-proof society.”

Shane’s book is both well-written and engaging as well as thoroughly researched. He relies both on personal observation from his time in the Soviet Union and archival research using what were, at the time, newly released Soviet documents. He paints a compelling and reasonably understandable picture of an element of Soviet collapse that we tend to ignore – the role that information played. At the same time, Shane interweaves an argument that also includes the traditional notion that an inefficient and sluggish economy also had a role in the system’s collapse. The Soviet Union was a country of immense wealth, and yet the rejection of economic reasoning and corruption at the heart of the system prevented it from prospering. Despite trying to deny these realities to the rest of the Soviet public, eventually – with changes over time and in technology – it became impossible to reconcile these differences in image and in reality, and Shane’s book does an excellent job of explaining this concept in a nuanced and clear way.

For Further Reading:

- Shane, Scott. Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union. Elephant Paperbacks: Chicago, 1995. Print.

The Nixon and Khrushchev Kitchen Debate

On July 24th, 1959, the U.S. opened the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park in Moscow. The display was an agreement between the Soviet and American sides to hold exhibits in each other countries, hoping to promote understanding through cultural exchange. The month before, the Soviet exhibit had opened in New York; in July, President Nixon went to Moscow to open the exhibit and to meet with Khrushchev for the opening. It was at this exhibit that a serious debate over ideology took place with perhaps the strangest backdrop for such discussion.

The exhibit was meant to showcase a typical American lifestyle. As Nixon was showing Mr. Khrushchev some new American color TV sets, a debate began regarding the merits of communism and capitalism, an exchange that took place through the two’s interpreters. While the dialogue took place in a number of the exhibits, most of the debate took place in a mockup of a typical American suburban kitchen.

While passing the TV sets, Khrushchev launched into an impromptu speech regarding the “Captive Nations Resolution” that had been passed by the U.S. Congress days earlier. The resolution condemned Soviet control of “captive” peoples of Eastern Europe, asking Americans to pray for their deliverance. Khrushchev denounced the resolution and then mocked the technology on display, announcing that Soviet technology would catch up with American gadgets and appliances within a few years. Nixon goaded Khrushchev further, telling him that he should “not be afraid of ideas. After all, you don’t know everything.” Khrushchev responded in turn, stating, “you don’t know anything about communism – except fear of it.”

With a crowd of reporters and photographers following, the debate continued into the space of a kitchen in a model American suburban home. As tension rose, with voices rising and fingers pointing, the debate went past treatment of women under the two systems and into the territory of nuclear debate. Nixon suggested that Khrushchev’s constant threats of the use of nuclear missiles could lead to war; he chided Khrushchev for constantly interrupting him. Khrushchev took Nixon’s words regarding the missiles and war as a threat, and warned Nixon of “very bad consequences” in return. Finally, perhaps feeling that the tension had pushed dialogue too far, Khrushchev said that he simply wanted “peace with all other nations, including America.” Nixon returned his deescalating statement by saying that he hadn’t been a very good host.

The next day the kitchen debate was front page news in America, demonstrating the importance and significance of cultural exchange. While the dialogue here did get very heated, both leaders clearly attached significance and meaning to the American cultural display beyond the banal. A suburban American kitchen and living room set became a demonstration of technological superiority and a higher standard of living, leading to a larger discussion regarding ideology, security, and national relationships. On the most basic level, both leaders saw such exchange as an opportunity to reach a potentially hostile foreign audience and to educate and enlighten that audience to the realities of their home culture.

For a partial transcript of the debate from the CIA Library, click here.

Sources:

The History of Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA) is an international multimedia broadcaster, now in service in more than 40 languages. VOA provides news, information, and cultural programs funded by the U.S. government. The VOA began broadcasting in 1942, and was initially meant to be a tool for combatting Nazi propaganda and misinformation.

In fact, the U.S. was one of the last world powers to establish a government-sponsored international radio service. Many other countries had already seen the power of international radio as a tool for foreign policy; the Soviet Union had built a center in Moscow and was already broadcasting in 50 languages by the end of 1930. By 1933, Italy, Britain, and France had already launched broadcasts of their own. In 1933, Nazi Germany also began broadcasting, focusing specifically on broadcasts of hostile and aggressive propaganda in other nearby countries and Latin America.

In 1941, Roosevelt established the U.S. Foreign Information Service (FIS), motivated by his belief in the power of American ideals and the need to communicate those ideals with foreign audiences. This belief is best captured by the man who would be the first director of the FIS and the father of the VOA, Robert Sherwood:

“We are living in an age when communication has achieved fabulous importance. There is a new decisive force in the human race, more powerful than all the tyrants. It is the force of massed thought-thought which has been provoked by words, strongly spoken.”

Faced with a second world war, and with both Japan and Nazi Germany using radio broadcasts to promote their own national agendas, the VOA was established as an organization to tell the truth, regardless of whether that truth was good or bad.

While support for the VOA dwindled in the initial years after the war, and along with it funding, the Berlin Blockade of 1948 changed many minds in Congress as it made apparent the need for an American voice internationally to combat hostile broadcasting from the Soviet Union and Soviet-controlled countries. That same year, Congress would also finalize the Smith-Mundt Act, which permanently established America’s international educational and cultural exchange programs that had previously been functions of the VOA. The need for exchange and an international voice was becoming increasingly apparent and vital for the coming Cold War effort.

In 1960, when the VOA had come under the authority of the new U.S. Information Agency, director George Allen endorsed the VOA charter which laid out the principles that would govern broadcasts. These principles were:

(1) VOA will serve as a consistently reliable and authoritative source of news. VOA news will be accurate, objective and comprehensive.

(2) VOA will represent America, not any single segment of American society, and will therefore present a balanced and comprehensive projection of significant American thought and institutions.

(3) VOA will present the policies of the United States clearly and effectively, and will also present responsible discussions and opinion on these policies.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) was established, the VOA established a daily flow of news and information into the region. In response to the requests of some Eastern European leaders who were seeking to establish new democracies, the VOA began broadcasting programs explaining the ways in which democracy and market economies functioned in the West. While the broadcasting of news and information to Eastern Europe and CIS countries was seen as a priority at this time, the VOA also continued to broadcast to regions throughout the world.

Today, the VOA broadcasts in 53 languages to audiences in every world region. While the VOA continues to broadcast, it has faced serious programming and budget cuts in recent years. As per their website, the VOA’s mission is still stated as “providing comprehensive coverage of the news and telling audiences the truth” and exemplifying the principles of a free press to international audiences.

Sources for Further Reading:

Book Review: The First Resort of Kings: American Cultural Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century, by Richard T. Arndt

In The First Resort of Kings, Richard Arndt sets out to detail the long history of American cultural diplomacy, its importance, and why this matters for American foreign policy today. Arndt starts with a brief and whirlwind history of cultural diplomacy starting from the Bronze age and continuing all the way through World War I in roughly 25 pages, meant to demonstrate cultural diplomacy’s longstanding importance in the foreign policy of virtually all global actors. Starting around World War I, cultural diplomacy as a foreign policy concept started to really develop in the U.S., and this is where Arndt truly begins his story. Focusing almost exclusively on the complex and at times infuriating inner machinations of the Washington bureaucratic structure, Arndt details cultural diplomacy’s golden age in America, and then its decline through the push and pull of bureaucratic politics and the pressure placed on the concept by those leaders and public officials who did not see the worth of cultural diplomacy in American foreign policy. Arndt argues, however, that cultural diplomacy is a crucial part of promoting understanding and tolerance between nations, and improving America’s image abroad at a time when such improvement is desperately needed.

Arndt, a self-described cultural internationalist, spends a lot of time focusing on the shifting of responsibility for cultural diplomacy to various agencies, offices, and bureaus. Initially a part of State, cultural diplomatic functions were, at one point, moved out of State and into USIA. Much of the debate for this initial movement out of State started with the first World War. Cultural relations were considered by many public officials as the perfect tool for disseminating information and the “American side of the story.” Arndt emphasizes this time as the point where the first serious schism developed among cultural diplomats – those who he calls “informationists,” and those who he refers to as “culturalists.” The culturalists believed in what Arndt refers to as a reciprocal flow of education, free from bias or attempts to propagandize. As Arndt defines this, he refers to exchange programs, American universities abroad, arts exchanges, and the like which he calls “mirrors” of American culture. Foreign audiences are provided glimpses into American culture, but the culturalists allow them to interpret or assign value to this cultural learning. The informationists, on the other hand, Arndt classifies as unidirectional propagandists – they provide “showcases” instead of mirrors, assigning positive value to positive aspects of American culture which they pick and choose to put on display, and essentially pitching America through cultural exchange with very specific intended messages. He likens the informationists to advertising agents and public relations specialists. The problem created by these informationists is that they undermine trust, understanding, and confidence in the U.S., which Arndt believes can be built gradually through cultural diplomacy as it was meant to be done, as opposed to an operation of spin-control. As Arndt states, “Education, in the cultural diplomat’s sense, is neither brainwashing, reeducating, nor reprogramming, but only a means of bringing out the best in people by showing them how to handle alternate truths (550).” Cultural diplomats do not predict where change from their cultural programs will lead, and they do not try to force it. They simply provide programs that reflect American culture and allow foreign audiences to decide how they wish to interpret them.

While Arndt makes a compelling and passionate plea for the revival of cultural diplomacy in its truest form, there are some problems with the book. For one, the book seems to actually be two separate books forced together – part history of American cultural diplomacy and part memoir. At a whopping 556 pages, Arndt would do well to edit and separate some of these pieces. Additionally, by focusing exclusively on the bureaucratic machinations in Washington that affected cultural diplomacy’s path, Arndt almost entirely ignores foreign perceptions until the end, as well as the roles that women and minorities played. This might not have been accident, however, as Arndt says at one point of cultural diplomacy’s decline under the Clinton administration that “…Clinton’s unrestrained political appointments primarily favored women and minorities over experience, as part of “making the administration look like America” – which created a stress on appearance over excellence that did not encourage the professionals (539).” I found this quote particularly disturbing, as it seems to imply that Arndt believes diversity is not an important concept for the American foreign service and perhaps even undermines its quality. If a true interpretation, this deeply undermines his argument that the best way to promote foreign policy and diplomatic success is to allow true and unfiltered exchange between peoples of different backgrounds, experiences, and cultures.

If you are able to accept that the book is written from the bias of the university-educated intellectual elite, this book is an excellent overview of the history of cultural diplomacy in American foreign policy, as well as a prescriptive warning that despite two decades of decline, our public diplomacy program (where the cultural programs are currently housed) can still be saved. Arndt details the problem of undervaluing cultural diplomacy especially in times of war. During the 40s and 50s, many American politicians deemed cultural diplomacy just another aspect of “globaloney.” The gradualist goals of the culturalists were not attractive when pitching to the decision-making elite, which opened the door for informationists to sales pitch cultural diplomacy as a public relations and propaganda tool – essential for wartime diplomacy and with a faster payoff, albeit short-term. Although the book is a frustrating chronology of the decay of American cultural diplomacy, Arndt ends on a positive note, saying that “rebuilding cultural diplomacy is not an impossible dream, only a long task requiring steady hands and an unusual kind of total U.S. national commitment, inspired by the kind of bipartisan friendship which Fulbright and Taft forged in 1945 (556).”

For Further Reading:

- Arndt, Richard T. The First Resort of Kings: American Cultural Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century. Potomac Books: Washington D.C., 2006. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment