Jennifer Chan, The McGill International Review

Kim Yuna, figure skating gold medalist, speaks as a bid ambassador for South Korea in 2011 https://flic.kr/p/9XWf3p

There has always been an inherent connection between sports and politics. In 19th century Britain, there was a movement known as “muscular Christianity” that emphasized the importance of schoolyard games and bolstering fair play to mold “future guarantors of the Empire.” The cooperation and collaboration intrinsic in team sports aid in nation-building by rousing patriotism and pride. Sportsmanship and camaraderie can strengthen domestic relations or can be magnified as diplomatic relations between states. As unlikely as it may sound, sports are an instrument of soft power. According to Political Scientist Joseph S. Nye, who coined the term in 1990, soft power is the “ability to shape preferences of others through appeal and attraction.” Soft power is not coercive like overt military or economic action; it is less risky but more difficult to wield. Especially in today’s consumerist society, the instruments of soft power are not completely under the control of governments. Rather, there has been a diffusion of power into the hands of corporations and independent organizations such as the International Olympics Committee (IOC). While it is difficult to quantify and measure soft power considering the fact that it is composed of a multitude of factors, the role of sports as a form of soft power is more relevant than ever as we look ahead to the 2018 Olympics hosted by South Korea in PyeongChang and the role of international organizations.

The Political Past and Present of the Olympics

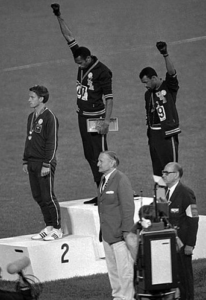

The Olympics have had a history of being a political stage and political device in itself. It exists as a space and an opportunity for diverse political actors to engage outside of formal political environments and institutions. International mega-sporting events can reflect the political climate and statements can be made by states through boycotts. Most notably, during the Cold War the United States boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow in response to Soviet involvement in Afghanistan. In response, the USSR did not participate in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. The IOC has also made political statements such as the banning of South Africa from participating in the Olympics from 1964 until 1992. This was done to condemn them for their domestic policy of apartheid. Thus, this decision not only supported the anti-apartheid movement, but also civil rights movement in the United States. Lastly, athletes themselves can use the games as a platform to make statements. Tommie Smith and John Carlos did in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics when they raised their fists in solidarity with the Black Panther movement, as did North Korea’s Hong Un-jong and South Korea’s Lee Eun-ju at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics with their selfie shared more than 18,000 times. Seeing the current tension between South and North Korea, North Korea has had the national policy of “Sports Diplomacy” since the 1980s. Promoting athletes who compete abroad with rewards such as state titles, and government awards, Sports Diplomacy aims to build image and trust. Sport exchanges such as the one struck between Kim Jong-un and former NBA player Dennis Rodman show the role private entities have in wielding soft power and enhancing cooperation.

Soft power aids countries by saving on the number of resources spent on pursuing external objectives. With the nature of the Olympics as an international spectacle, they attract a large proportion of the global audience; thus, the Olympics are an ideal stage to showcase international cultures and promote shared values. The 2012 Olympics were watched by more than 50% of the world’s population. Since 2012, global user numbers have gone up by more than 80% in the past 5 years. Thus, the 2018 Olympics are expected to connect to a larger audience due to the utilization of various social media platforms such as snapchat, diversity of advertisement mediums and more corporate sponsors. The British Council research showed that on average 35% of people were more likely to visit the UK after the 2012 Olympics.

While hosting the Olympics is a practice of soft power and public diplomacy, it requires a lot of economic strength and national legitimacy. This is why prior to the 1980s, the majority of host cities were developed nations. Hosting shows signs of credibility and economic power and opportunity. The plethora of hosting benefits such as being able to increase a nation’s image, bolster nationalism, demonstrate credibility, show economic stature and competitiveness has resulted in a surge of bids to host from BRICS. By doing so, they show their political willingness and economic ability in the international political arena. Hosting the Olympics has also become a way for states to strategically compensate for public diplomacy, as hosting shows connectivity to the international community and commitment to universal norms. Despite past human rights abuses, undemocratic governance, and a lack of conformity to the global capitalist economic system, China was selected for the 2008 and 2022 Olympics. Especially with China feeling less impact from the 2008 recession, the country blossomed as a global superpower post-2008 Olympics. Sheffield Hallam University compared the medal count of G7 countries and BRICS and found that in 1996, the G7 had twice the medal count of BRICS, but by 2008, the medal gap had been reduced to a difference of 10%. This is significant as playing sports professionally is classist in that many sports require a certain level of income to be able to afford equipment, training, and the time to practice. Thus, the numbers represent a narrowing in economic disparity, but they also show that investing in sports is a development strategy that bolsters growth internationally and domestically.

Construction for the Maracanã Stadium where the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympics opening and closing ceremonies were held https://flic.kr/p/9w4vbY

In addition to strengthening foreign diplomacy, hosting the Olympics can also be a way to arouse domestic pride and aid in reconciliation. An example of that is post-apartheid South Africa, the host of the 1995 Rugby World Cup, 1999 All Africa Games, and 2003 Cricket World Cup. Their success and eventual hosting of the 2010 FIFA World Cup signified restoration of international credibility, as well as garnering South African pride and strengthening national unity. However, the desire to strengthen international prestige can also shadow domestic issues. During the 2016 Olympics in Brazil, the national income disparity, seen through things such as poor public health and low investment on public infrastructure was at the forefront of domestic issues, yet billions of dollars were being pumped into facilities that were not universal for the population and were deserted after the games ultimately resulted in lower public trust.

The Corporatisation of the Olympics

Gold medal game between Canada and Sweden at Sochi 2014. The entire Canadian roster was composed of NHL players and Sweden, save for one, was as well. https://flic.kr/p/oMku27

This sheds light on issues of funding as every two years we see host countries attempting to throw bigger opening and closing ceremonies and better facilities, hence the integral role of sponsorship that has resulted in growing corporatisation of the games. This indicates that the Olympics have slowly become more of an economic instrument rather than a political one. For example, the National Hockey League (NHL) commissioner Gary Bettman announced in April that they would not have NHL players play for their national teams in the 2018 Olympics. The reasoning behind this decision was that the NHL was seeking more compensation from the IOC as they wanted the games to be “worthwhile ventures” for owners as they would need to shut down the league for three weeks, despite the fact that they have done so every four years since 1994. In response to this, International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) President Rene Fasel has spoken out and continues to push for NHL participation as he sees it as an opportunity to bolster a stronger platform for the sport on an international stage. At the end of the day the corporate interests of the NHL have been prioritized but the fans, the sport, and the players lose (Sidney Crosby might never play in an Olympics again). This decision was made on a purely economic basis, yet it has political repercussions. There has been backlash on the IOC’s end as they tie the NHL’s participation in the 2022 Games in China to their participation in the 2018 Games and if this occurs it would affect Canadian foreign relations. The political ramifications of this decision can be seen in Canada’s foreign relations. It is estimated that Canadian economic activity related hockey brings in over 11 billion dollars annually. Hockey is a source of Canadian pride and patriotism. Recently, it has also become a source of diplomacy between China and Canada and with Canadians making up the majority of the NHL but a minority of franchise owners, this decision could translate to a loss in both diplomatic opportunity and soft power for Canada.Currently, Lee Hee-beom, the president of the Pyeongchang Olympic organizing committee, is still pushing and hoping for a reversal of the decision by collaborating with Fasel, the IIHF and with IOC president Thomas Bach to sway the NHL into participating. Canadian skater Brian Orser commented in response to the NHL’s decision that “it’s a shame…the business is more important than the sport.”. The current situation between the NHL and IOC makes it evident that corporatism undercuts the legitimacy of the Olympics and threatens the ‘soft power’ of sports in foreign relations.

Looking to the 2018 Olympics

Strengthening foreign relations is key to tackling current international challenges such as global warming and pandemics. With the 2018 Olympics being hosted in PyeongChang there is an opportunity for newly elected South Korean president Moon Jae-in to utilize the games to potentially ease growing tensions in the region. It is expected that his policies will facilitate stronger relations with North Korea and will be reflective of the Sunshine Policy that advocated for diplomatic conversation and negotiations with rewards in exchange for North Korean compliance with denuclearization. The Sunshine Policy was implemented by Kim Dae-jung in 1998 and President Moon was chief of staff during Roh Moo-hyun’s administration between 2003-2008 where the policy was continued. During the Sunshine Policy era between 1998-2007, North Korea and South Korea marched together as one during the opening ceremonies of the 2000, 2004 and 2006 Olympics.

In addition to this, President Moon ran on the platform of reviewing Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD), a US missile defense system that has generated tension between China and South Korea and has exacerbated tensions between South Korea and North Korea. In an era marked by increased information and diffusion of power, the Olympics will become an increasingly important part of effective foreign policy strategies. More than just a game, sport is an expression of soft power.

No comments:

Post a Comment